THE SURRENDER OF MAN

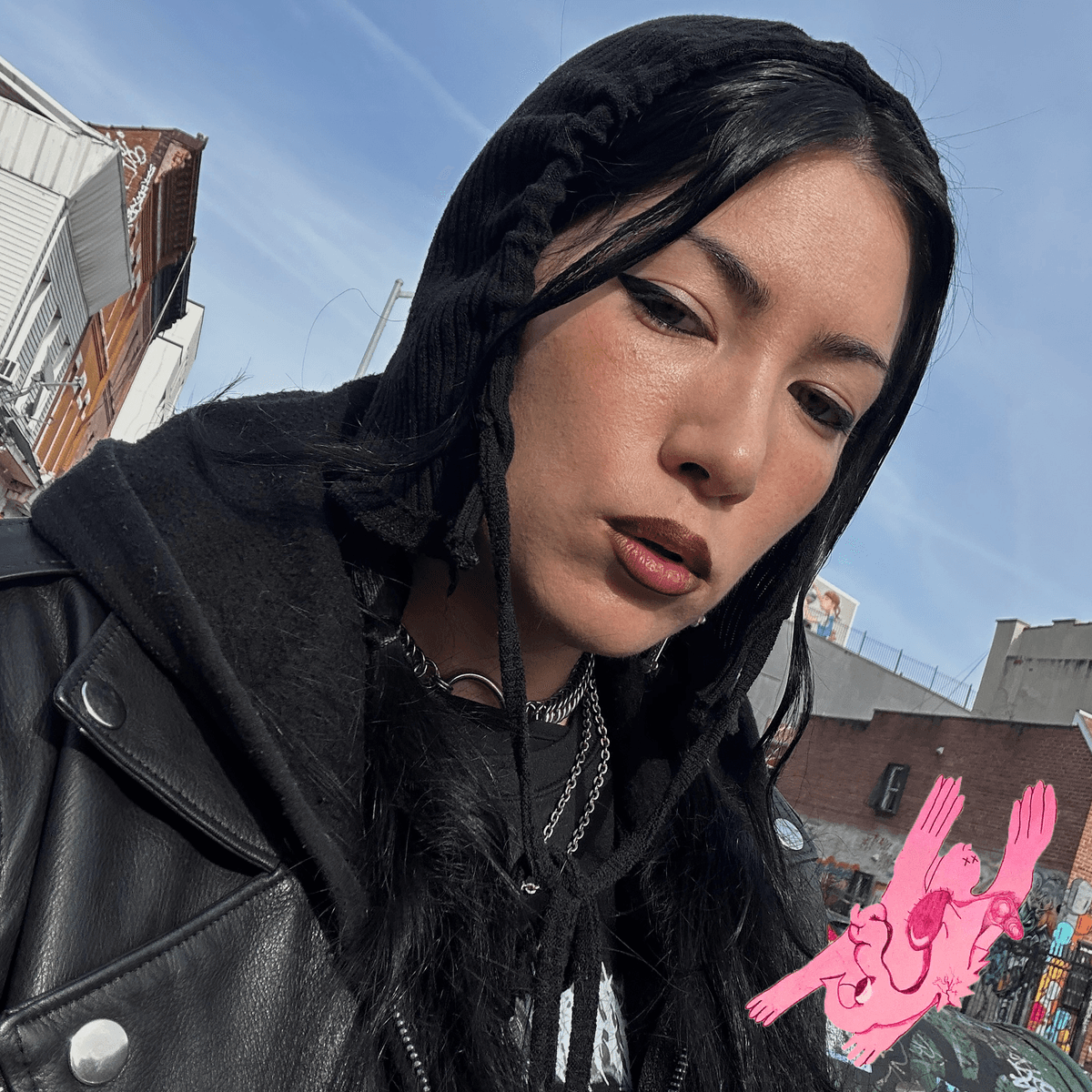

Naomi Falk

In addition to writing books, I also make them. I think having a trade helps me see artists more eye-to-eye. It felt inevitable that my work would be about the work of other artists.

TESS POLLOK: You’re a writer and editor juggling many jobs in publishing! You have a full-time position as the Production Director at powerHouse Books and you’re also the Senior Editor at Archway Editions. Your first book, The Surrender of Man, is forthcoming from Inside the Castle. I’m interested in how you would classify this work; I’m hesitant to use the novel designator because it’s very experimental and genre-fluid. I see it as an experiential text that’s preoccupied with art history. Who were your influences while writing?

NAOMI FALK: Clarice Lispector is a huge influence for me. One of the most profound experiences I ever had as a writer was reading Água Viva in grad school and later teaching it to writing students. That book in particular excels at pulling together the strange fabric that exists between reality, poetry, and fiction–trying to elicit that feeling in my readers was important as I was working on The Surrender of Man. I think she’s more elusive in that book than I am in mine, but I wanted to capture the bewitching quality of her writing in my own work. Another formative influence for me, who I think is mentioned in the marketing copy, is Jean Rhys. Like many writers of my generation, I loved Wide Sargasso Sea. Obviously, Marie NDiaye’s Self-Portrait in Green. Maybe this isn’t fashionable to say, but Flannery O’Connor, as well. I grew up reading her short stories, but I just read her novel Wise Blood for the first time and it completely changed my life.

POLLOK: [Laughs] Flannery O’Connor will never go out of style. Any non-literary influences on the book?

FALK: Yes, actually. So I’m also a classically trained pianist and I was thinking a lot about composition while working on the book. I love Romantic composition, like Franz Lizst. I think he’s a huge influence on how I write because of the liberated punctuation of his music, which feels akin to how I try to write, either not punctuating or separating certain thoughts or clauses from one another and allowing all of it to inhabit a singular, more big-picture landscape.

I also listen to a lot of heavy industrial and black metal, but I don’t think that inspires my prose. Or, it does inspire my prose, but in an inverted way–I think my prose is a lot more folk-centric, possibly in response to me listening to music like that all the time. [Laughs] I like how folk music and folk stories are handed down generationally and that’s a feeling I try to evoke with the more lyrical parts of my work. I want to dig down to the feelings of lightness and deep time that folk writers capture and place less emphasis on being stylish or contemporary.

I would also say that all the artists I explore throughout the book are inspirations to me, as well. Leonora Carrington, Remedious Varo, and Mary Shelley–that Gothic horror type beat that I love. Another artist I’ve been thinking of a lot over the past few years is Peter Sinfield, the original lyricist for King Crimson. I love that medieval sound and the way he wrote those first three albums has always stuck with me.

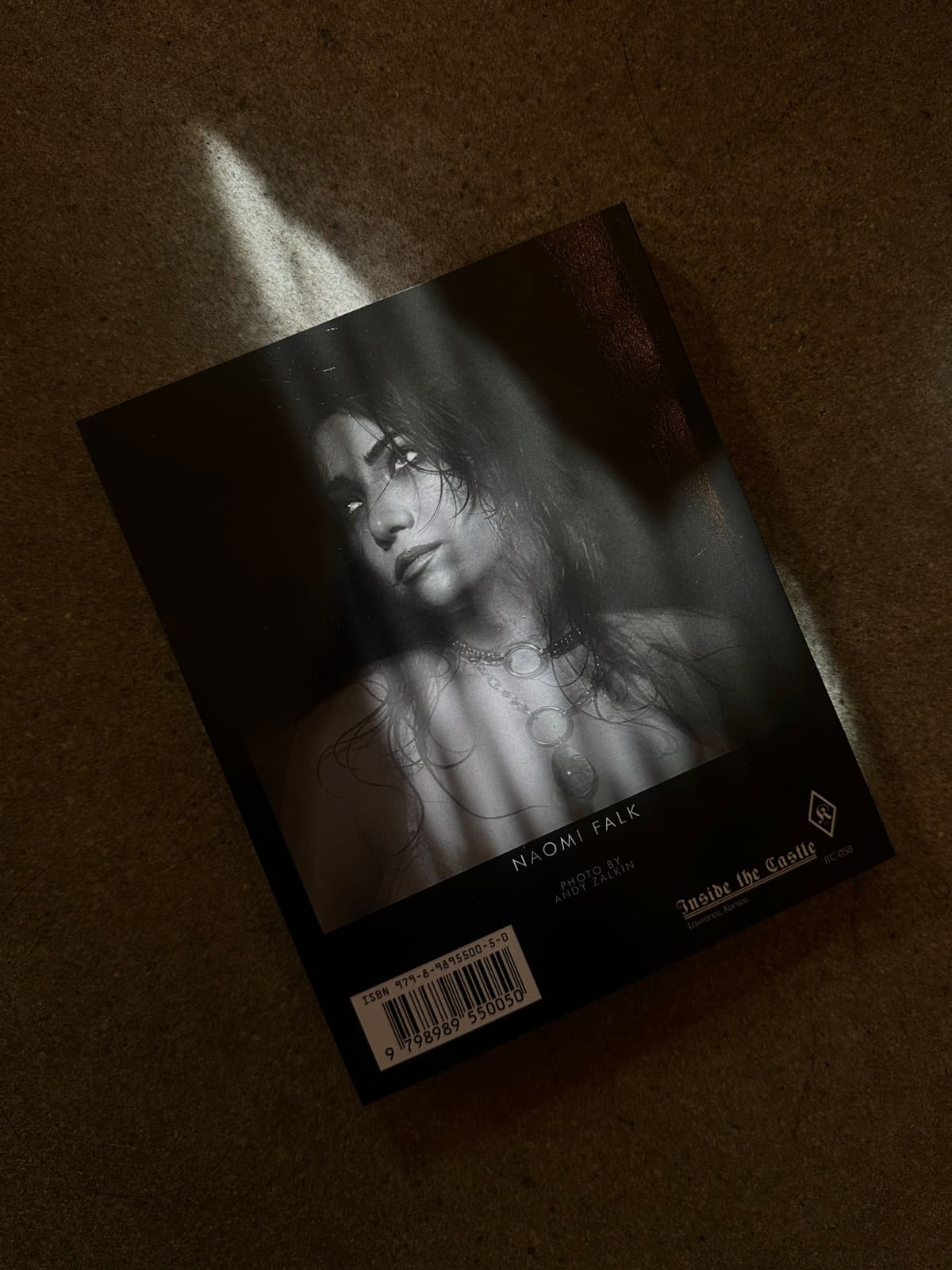

Front and back color illustrations from THE SURRENDER OF MAN

POLLOK: You love King Crimson? Have you ever seen Mandy? That’s one of my favorite movies.

FALK: Oh my god! I love Mandy!

POLLOK: It’s a comfort movie for me, I’ve seen it so many times. I think it gets overlooked as a genre film because of its love for King Crimson but that’s such a snub. It’s a masterpiece.

FALK: There’s so much to love about that film. The music is incredible and the cult narrative is just so much fun to watch. I think you’re completely right that people overlook it–it’s a masterpiece, aesthetically, it just has such strong muscles.

POLLOK: What made you interested in playing with the form in your work?

FALK: I actually studied nonfiction while in school, which I think is evident in the book. So much of the fabric of my brain as an artist is stimulated by other people and I don’t differentiate based on medium. It felt inevitable that my work would serve the stories of artists. While I was writing the book, I was working as the Editorial Director at Ki Smith Gallery and also at MoMA–it’s funny because “write what you know” is such a predictable idiom when it comes to writing, but I really did have it on my mind when I was working on the book. When people talk about artists who impacted them, artists who really saved their lives, they’re often talking about musicians and filmmakers. For me, that medium has always been visual art and writing. But something I learned from my experiences in the fine art world is that it has a lot of barriers to entry. It feels a little more separated from the other mediums. So I knew what I wanted to do with the book was write about art from a more personal perspective that lets the reader inhabit the emotional experiences and emotional worlds I’m feeling when I connect with these artists. It feels like a way of democratizing access to art.

POLLOK: I think the word democratizing is a great one to describe your work. Even though it’s about the work of artists, I hesitate to use the word criticism to describe it. Because you’re not really offering institutional critique of these works, you’re surfacing and sharing an emotional experience you’re having with them.

FALK: I don’t see myself as a critic, that’s true. I think of myself as someone who works alongside artists. I’ve engaged with art criticism and have written about exhibitions in the past, but I think part of that has to do with my trade. In addition to writing books, I’m also a designer and I make and produce lots of publications, formally and informally. I think that helps me see artists more eye-to-eye. It’s like that clown-to-clown communication meme. I see them more as peers than as subject matter.

Two publishers in conversation

POLLOK: What drew you to the work you feature in the book?

FALK: They’re not all my favorite works, personally, but I think about them as a collection of pieces that I consider to be profound or impactful in some way. I don’t think a piece has to be your absolute favorite for it to make a strong impression. I also wanted it to be an engaging and exciting journey for the reader to read about all these art pieces, so I tried to include things that felt both light and heavy. I have a very specific vibe as a person, so I wanted the audience to be surprised by some of my choices. Incidentally, some of them are my favorites. But for the most part, I think of the book as starting off with works that are maybe more dense and self-contained and expanding over time into works that are airier and maybe more visually expansive. This is meant to help shape the larger emotional journey of the book.

POLLOK: Do you see The Surrender of Man as relating to your other work in writing or publishing? I only ask because you seem to wear many hats; I’m wondering to what extent you feel there’s overlap between these different creative practices you’re cultivating.

FALK: Oh, 100%. In a few months, we’re bringing a book I’m very excited about back into print–aesthetic theory from the very late 1800s, the book no one asked for. [Laughs] We think of aesthetic qualities as being tactile but there’s so much abstraction behind how we think about material and imagery. I think I want people to see themselves reflected in art and culture, you know, the big hope with these projects is that I’m making these topics more accessible to people and helping them relate these concepts to their lives.

NAOMI FALK is a writer, editor, and book designer based in New York City. Her first book, The Surrender of Man, is forthcoming from Inside the Castle later this month.

TESS POLLOK is a writer and the editor of Animal Blood.

← back to features