SIDEWAYS EXPERIENCES

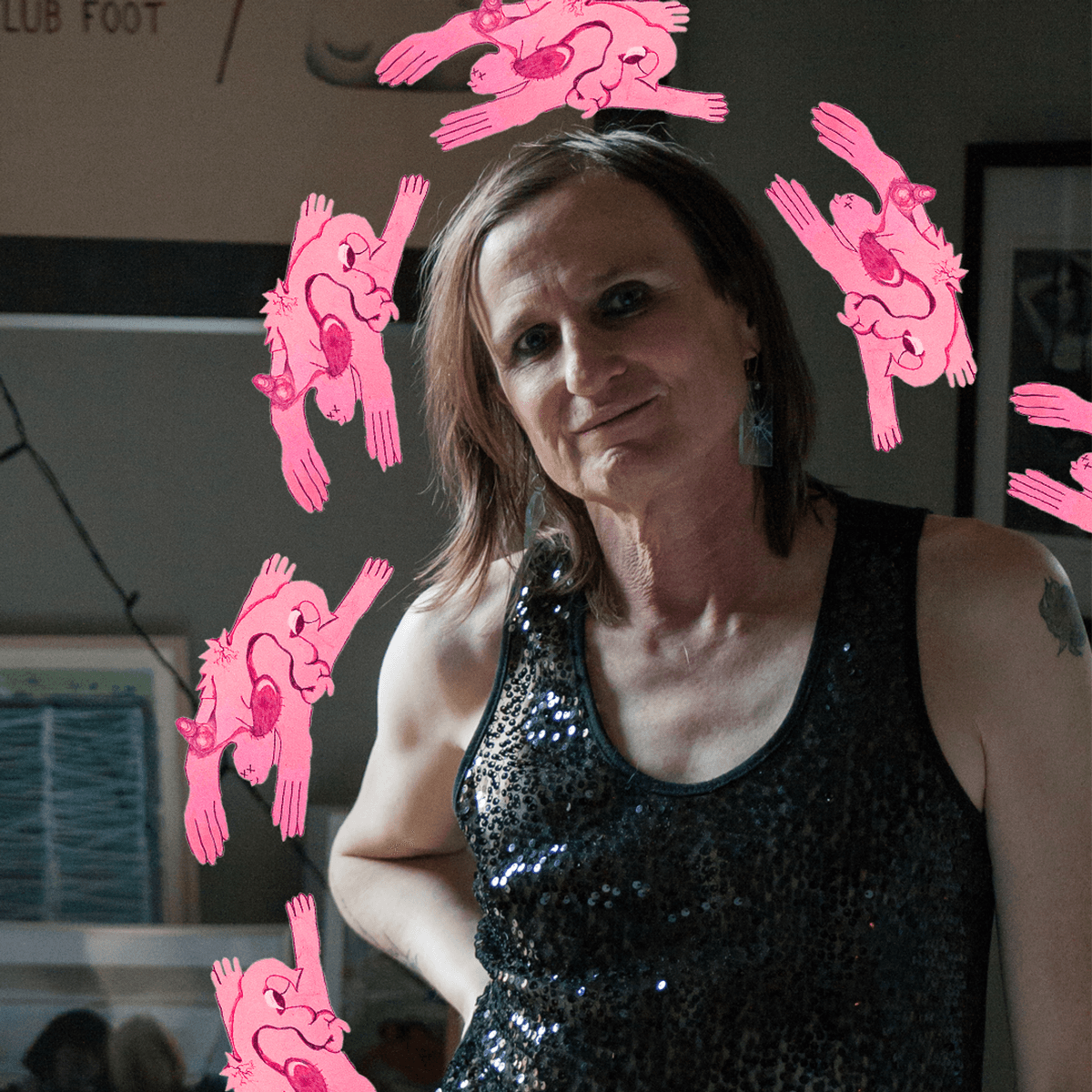

McKenzie Wark

My writing proposes an alternative to the temporal structure of desire…the structure of desire is always about the current lack of future possibilities that will remain unrealized to re-substantiate the lack. I imagine a future of ongoing-ness that isn’t oriented towards our lack.

TESS POLLOK: I’m a huge fan of Capital is Dead: Is This Something Worse? so I was really excited to see you put out two new titles this year: Raving and Love and Money, Sex and Death. You’re best known for writing theory, but your recent work is more personal and autofictive. How did it feel to make that transition?

MCKENZIE WARK: It’s actually not the first time I’ve tried autofiction out, although it is the first time I’ve done it in such a broadly visible, publicized way. I started out writing autofiction back in Australia in the ‘90s. I pivoted more towards theory as I had to make a career as an academic after I emigrated to New York, but the form and function of my work changed again when I came out as transsexual in 2018. That made me more of a marked subject and it became a conceptual problem: how do you write from that point of view and overcome that discount against your humanity? I think of Reverse Cowgirl, Raving, Love and Money, Sex and Death, and Philosophy for Spiders as continuous parts that tell an unfolding story since I came out.

POLLOK: Interesting, I didn’t realize you’d already written so much about your own life. And now you’re writing against and/or through the experience of transitioning?

WARK: I’m not sure. I call this new type of writing I’m doing autotextual because it’s somewhere between autofiction and autotheory. Those are cursed genres. I’ve always loved cursed genres, things everybody looks down their nose at. In terms of how it relates to my transition, I wrote Reverse Cowgirl before I went on hormones because I thought that would fuck up the writing–and it really did. I didn’t write anything for three years. Reverse Cowgirl was a book about thinking through the past at that moment of decision. What I like about writing autofiction and related genres is that they don’t make the same kind of truth claims that memoir or biography do, they’re not claiming to reveal the true essence of inner subjectivity. I think of my recent books as experiments in the first person, ways of tracking and drifting through various sets of experiences. Raving and Love and Money are more concerned with otherness. But, again, these books have all been part of an ongoing series of experiments for me, and it may or may not be time for me to mix it up again, we’ll see. I tend to do a different thing every three to five years.

POLLOK: I wanted to ask you specifically about dissociation, which you reference frequently in Raving and some of your other books. I’m fascinated by how you detach from clinical associations with dissociation and instead use it to interrogate these transcendental experiences people have with daydreaming and dancing. I was drawn to a quote from Adorno you used in Raving to describe how “listening subjects lose their freedom of choice and responsibility” when they’re lost in the music. It was interesting of you to put dissociation in its own aesthetic context.

WARK: Completely, and I try to distinguish between types of dissociation. I don’t want to be disrespectful of clinical dissociation, which can be a very life-degrading condition for those suffering from chronic or complex trauma. But, absolutely, I’ve been interested in dissociation for a long time. The first time I dissociated was when I was 6 and my father told me that my mother was dead; it was like I just disappeared. Someone pointed out to me that I visited this formative experience in the first pages of Reverse Cowgirl and after that I became interested in what you can do with dissociation when it isn’t debilitating. In Raving, I was searching for ways of dissociation that are enabling by approaching raves as a structured environment designed to elicit a certain kind of dissociation–a state of shifting the senses away from the visual and towards the kinesthetic. I was also thinking of how trans people frequently dissociate due to dysphoria and how the rave spaces I frequent are trans and queer communities that badly need this. So the approach is broadly grounded in disability studies, in understanding that disabilities can sometimes also be different abilities, in uncovering how these can be useful. What is unique about our place and time right now that raving is so popular and that so many people are craving the opportunity to dissociate?

POLLOK: How long have you been interested in raving?

WARK: I was a raver in the ‘90s but I just didn’t get it back then–I didn’t understand what we were doing. After separating from my co-parent and going through my transition, I discovered I really loved raving and actually needed it. For a lot of queer and trans people, it’s not just entertaining, it’s sustaining.

POLLOK: I wanted to talk to you about gender and masculinity in music spaces, queer spaces, and rave spaces. You quote Mark Fisher in Raving but distance yourself from his thinking. You call him overly masculine. What do you think about Fisher’s thinking?

WARK: Mark’s certainly not the worst offender with that. Raving is among other things a consideration of Mark’s idea of acid communism, although it seems clear he didn’t actually do acid—”well, honey, why not?” I think he can be too detached and there’s a reluctance on his end to find the sideways collective experiences that really unify the topics he talks about. I always felt that was a missed opportunity in Mark’s work. I understand why his writing works, but I’m interested in offering a different set of experiences and perspectives to examine these ideas.

POLLOK: I’m interested in what you think masculine thinking is, in general. Not tied to Mark Fisher at all.

WARK: Is there masculine thinking? I know there was an attempt to do the opposite, with écriture féminine–the French attempt to feminize writing and to write otherwise. But I think that type of thinking tends to get reductive on both ends.

POLLOK: That makes sense. In Raving, you characterize contemporary life as an age in which we’ve become disinterested in our own desires, as “they always live in the future, and there’s not much of that.” What’s causing you to describe life in this way?

WARK:The structure of desire is always about the current lack of future possibilities that will remain unrealized to re-substantiate the lack. That’s the structure of it. There’s something essentially modernist and also theological about the whole concept of desire and future time. Instead of desire and lack I think about wants and needs, a question of examining how we gratify different wants and needs across various temporal frameworks. That’s what a lot of trans lives look like anyway. Most trans people I know don’t expect futures. It turns out there aren’t a lot of viable futures for any of us on the macroscale and that’s a hard thing to acknowledge and think about. If we’re not building our desires around our future, what would it mean to not desire them anymore? To play instead with wants–to sustain the body, or stave off boredom in the present? I think of Raving and my preoccupation with dissociation as a part of my interest in ongoingness, which isn’t about there being a future towards which one orients one’s lack. It’s more about adding one moment onto the previous one, starting in the present. My writing proposes an alternative to the temporal structure of desire.

POLLOK: Yeah. I can really relate to that as a young writer who graduated, you know, into the pandemic–seeing this certain framework in my mind of how success as a writer was going to play out and then watching all of these things end up obliterated or not that real in the first place. At first it’s like internal culture shock, you’re, like, “Well, what am I going to do with myself, now?” You can plunge into nihilism if you’re spinning your wheels really hard. But with this project and others I try to express myself with what resources I have and make the most of that.

WARK: I’m in a similar position as a provincial outsider who’s somehow managed to clamber aboard the ship of academia only to find its sinking anyway. Higher education is clearly on the decline in the United States. When I’m talking about experiences of sideways time I’m interested in how we can make time with our friends, how we expand life for each other, be creative and find other modes of time outside the game of desire, lack, the future and all that. One might still want to build things, but the how of building matters. How can we live without sacrifice to a fantasy of the future?

POLLOK: I’m thinking now of our interview with Whitney Mallett of the Whitney Review because she mentioned the robust public arts funding in Canada and how it incentivizes artists but also has its drawbacks. Did you feel better living and working as a writer in Australia, England, or the United States?

WARK: Working and being able to make a living as an artist or writer is definitely very different depending on where you are. There’s an arts funding apparatus in Australia that tends to orient us towards the state, so, there’s grants, subsidized venues, and publications–but the downside is that it’s a part of an imagined community of the national project, so that comes with all the limitations and internal suppressions that you would expect. I was very lucky to get a job as an academic in New York City and be able to stay. I’m not really cut out for the national cultural undertaking of Australian letters and I’m not really cut out for the American academic landscape, which mostly happens outside major cities and requires a kind of academic pedigree and network I just don’t have. So I’ve tried to figure out how to be a writer of a different kind, outside those spaces a bit.

POLLOK: You’re describing a lot of conventional routes to “success” that you haven’t taken. What advice would you give other young artists who are making similar difficult decisions about their careers?

WARK: To work whatever advantages you have and not be ashamed of it. Try not to be too competitive, be wary of rivalry, resentment, all that bad affect. Make collaborative projects. They’ll fall apart but that’s fine. Be generous with peers but ask to get paid what you are worth. Recognize that until you’ve been around for a bit you might not be worth much. It is sometimes okay to work for free but only if there is some tangible benefit. Keep an eye on trends but don’t follow them. Show up for others. Develop a solid work ethic. Learn to live cheaply. When you sell out, get a good price. All of the culture industries, just like the academy, are broken on the economic level, so maybe don’t quit your day job.

POLLOK: Being a culture worker or creative can be insanely depressing at times. I relate the dysfunction, on an increasing scale, to how corporate or disembodied the position is.

WARK: Yeah, exactly. The thing about rich people is that they’re both boring and bored as fuck. You can make a lot of money by being their entertainment. This is something I’ve learned from a lot of close friends who are sex workers; I’ve learned new ways of thinking about money and boundaries from them.

POLLOK: I want to keep up the focus on Raving. Were you thinking about the religious context of the transcendental experience at all? The mystical quality of the writing reminded me of the Greco-Roman mystery cults, Dionysian worship, that sort of thing.

WARK: Oh, completely. There’s overlapping literatures about rave, nightlife, queer nightlife, and religious experiences–I’m totally aware that there's an existing literature here that I’ve stepped into. But I felt like I had a unique and specific experience to speak to with queer raving in New York City at this time. I thought the language this particular world needed was different from what I was reading. I did a lot of interviews for Raving and people kept giving me propositions from existing language about what it was about: So you’re saying raving is utopia? So you’re saying raving is transcendence? So you’re saying raving is resistance? I was, like, “No, no, no.” For me it was about blending these different perspectives and writing something new, not using language from the past.

McKenzie Wark is a writer and theorist based in New York City. Her most recent books, Raving and Love and Money, Sex and Death, are available through Duke University Press and Penguin Random House.

Tess Pollok is a writer and the editor-in-chief of Animal Blood.

← back to features