PURE ART, NO CONTEXT

Parker Ito

Gay NFT is where the avant-garde is located in contemporary art right now, both in its aesthetics and dissemination. The mainstream art world does not have any idea what the fuck these projects are but when I look at this Gay NFT shit it genuinely feels like something that hasn’t existed- it imagines a new world.

TESS POLLOK: You’re a contemporary painter and multimedia installation artist whose work frequently references iteration, irony, and the internet. I think most of our readers would know you as the artist behind Made in Heaven / En Plein Air in Hell (My Beautiful Dark and Twisted Cheeto Problem) at White Cube back in 2014. Are you still looking at the world through a post-internet lens or have your interests changed? What are your upcoming projects like?

PARKER ITO: It’s not upcoming, but over the past weekend I was at Wesleyan University to install A Lil’ Taste of A Lil’ Taste of Cheeto in the Night, which is a smaller version of show I opened about ten years ago in a warehouse in downtown Los Angeles. In my opinion, it is the most important work I’ve ever done. This is also the first time I’ve ever reinstalled a past show and it feels really strange. Other than that, my current and upcoming projects are all NFT collections.

POLLOK: I’m really interested in your NFT projects and your thoughts on the NFT sphere in general, but I have to ask: what makes A Lil’ Taste of Cheeto your most important work?

ITO: A number of reasons. In terms of production, it was one of the most intensive installations I’ve ever done: I spent two years working on it, had ten people helping with production at my studio, plus an additional five fabricators. When I look at what I’ve focused on with my work over the past ten years, I feel like it really sums up what you could consider to be my “gesamtkunstwerk.” Out of all of my exhibitions, I think it’s best at showcasing the breadth of my practice- incorporating sculpture, painting, and video works to create an installation environment.

A Lil’ Taste of Cheeto in the Night, 2015

Courtesy of the artist

POLLOK: I’m happy the Wesleyan students got to see it, they really needed that. I want to talk also about your forthcoming NFT projects, but, correct me if I’m wrong, haven’t you already launched an NFT collection of procedurally generated oil paintings?

ITO: Yeah. I’m working right now on some newer NFT projects, but that was the first one I released. I got interested in NFTs back in 2021 when people started releasing collections and there was a bull run of super crazed market speculation around art on chain. It was all so unhinged and NFTs really earned a bad reputation in the mainstream art world; it was, like, instant scorn. But I felt like a lot of the opinions formed around NFTs at that time had to do with the aesthetics of those initial popular collections–most of them just looked terrible. I didn’t pay much attention to NFTs over the past couple of years. At the end of 2023 I got asked to do an NFT project and I started spending a lot of time on Twitter and stumbled across some newer projects that artists were developing on Solana. For many years Ethereum had been the designated fine art chain. This new community that organically evolved around Solana has been referred to as” Gay NFT” or sometimes “Avant NFT”. All of the projects, aesthetically, really spoke to me. This got me really inspired and now I’ve integrated into the scene, and I feel somewhat embraced by it.

My upcoming NFT project is going to be smaller than my first one. The first collection had 10,000 NFTs. This new one is only about 50 to 70. But it’s playing on similar themes- I’m taking traits from the first collection and integrating them into this collection in a different way. This new collection is heavily inspired by the aesthetics of Todd McFarlane’s Spawn animated series. What I want to do with this new NFT project is to redraw the assets from the last project but imagine them “in the shadows”. The central figure that recurs in this project is a character that’s representative of me, one that’s recurred in my work for a while in the form of a knight.

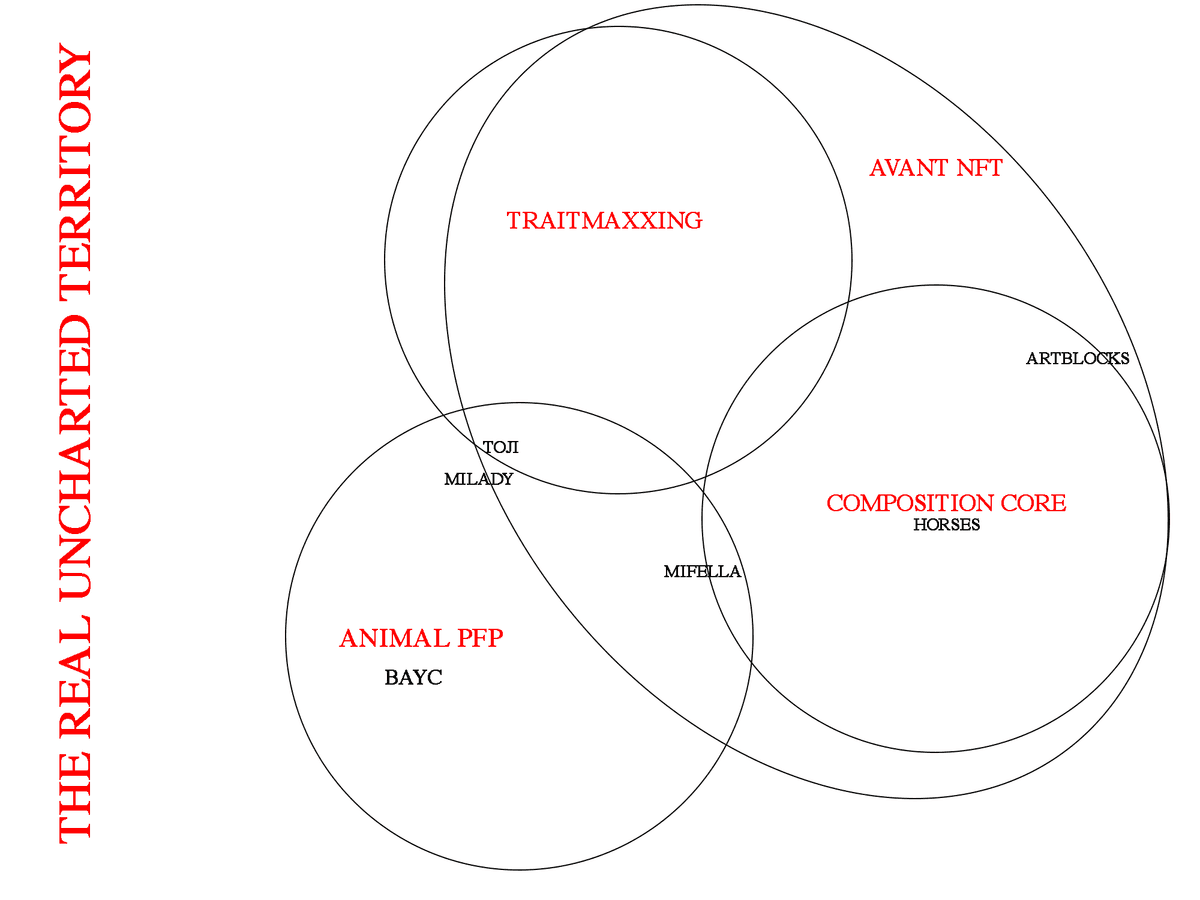

One of the common aesthetic sensibilities in the Gay NFT scene is this thing called “traitmaxxing.” That’s when you have a large number of traits, and often use a compiler program like Hashlips to generate these hyper-layered, densely collaged images. This aesthetic is not so different from the paintings I was making ten years ago, so it’s cool to see an entirely new iteration of it emerge online and be reinspired by that.

POLLOK: Who are some of the artists you admire in the Gay NFT scene? Are there any specific collections you would consider favorites?

ITO: So many. A big one would have to be Tojiba CPU Corp. Brand Manager from Tojiba released a collection called Horses that I think is brilliant. Drifella 2 by Evil Biscuit– I think it’s agreed upon by pretty much everyone in the scene that this is the most influential collection in Gay NFT. Another collection I saw early on that was very inspiring is called Self Driving Megaworms by KID Anthrax. What else? I think Supermetal Bosch is insanely talented, he made Little Swag World and Super Metal Mons. I’ve been thinking a lot about Little Swag World lately because I don’t completely understand how it was made, but the way that Bosch used AI to create it is very inventive. I don’t know anyone who’s using AI like that.

Evil Biscuit Drifella 2 NFT

Courtesy Twitter

Graph of aesthetic overlaps in Gay NFT projects

Courtesy Tojiba CPU Corp

If Record of Hyperwar is still mintable when this comes out people should definitely grab some of those. Another NFT collection I really loved was Little Fellow by Jim Spindle. Also, Solfis and Solfus Sisters by Dido deserve shoutouts. Another classic project is Squishy Drifters by Fairy Baby. A lot of these projects are expanded PFP projects–Squishy Drifters, for example, is a collection of cars but they act as non-human avatars.

POLLOK: PFP–that means profile picture, right? I’m glad you brought that up and also that you mentioned that your first impression of NFT projects was that they were ugly. I couldn’t agree more. When I first heard about the concept of online art collections, I imagined digital versions of the type of art I saw in museums. I was so confused when the first popular projects were things like Bored Ape Yacht Club (no hyperlink, sorry) and CryptoPunks. I didn’t understand why artists’ first instincts were to create, essentially, IMVU characters for virtual adventures? Like, what? I found myself warming up to them more as they branched out aesthetically. For example, I remember really liking Galerie Yeche Lange’s Pie Keys when they first came out.

ITO: Totally. The PFP format, the profile picture format, is the default NFT format for mainstream NFT projects. I think it’s interesting that a lot of those early projects were developed by people who didn’t necessarily consider themselves artists. Many of those collections weren’t received as art and thought of as being something more akin to a collectible, and I would say this is sort of the first thing that comes to mind when people hear the word NFT. What I like about the Gay NFT scene is that they’ve taken the structural remnants of the PFP format and gone completely insane with it. They’re doing experiments with AI and layer variation that start to make the avatar figure in the NFT just completely illegible. To me, Gay NFT is where the avant-garde is located in contemporary art right now, both in its aesthetics and dissemination. The mainstream art world does not have any idea what the fuck these projects are but when I look at this Gay NFT shit it genuinely feels like something that hasn’t existed- it imagines a new world.

POLLOK: It’s interesting, some of the internet/post-internet artists I’ve worked with completely embrace NFTs and others feel very excluded. Do you find, as a traditional artist in the internet/post-internet space, that it’s a worthy inheritor of the title?

ITO: I came up as an internet artist and many of the artists I worked alongside in the net art scene transitioned to the mainstream art world and were labelled post-internet, including myself. I see NFTs existing in three intermittent areas right now: there’s the super tech/crypto bro utopia space, which I don’t relate to at all. This is the space that embraced a lot of the hyper-speculation and, to me, is where things are the least interesting aesthetically. I think that space in particular responds to a problem the contemporary art world has had for a long time, which is that it wants to break into the tech world and find a way of harnessing the collecting power of that market. Tech people have a lot of money but maybe don’t see the value in buying contemporary art. Something like an NFT, which they can speculate on and watch accumulate in value, is much more appealing to them. There’s another scene loosely called the Ethereum Fine Art Network (EFAN), which has several artists from my internet art days who have made the transition to developing NFT projects. It’s situated in a fine art context that feels very different from the tech bro side, but there’s a technological element to it that I’ve never resonated with. There’s, like, a lot of glowing lines and coding of tessellating shapes.And then finally, there’s the Gay / Avant NFT scene which I think is making exciting and avant-garde art. Some of the artists in this scene ended up turning to this space because they felt burnt out by the darkness of the mainstream art world and NFTs don’t rely on that world.

POLLOK: Yeah, I mean, I can completely understand that. Reference for our readers–though certainly not for you–is that your own work was caught up in a bubble of hyper-speculation that saw prices rise throughout the early 2010s before they abruptly crashed. Obviously, the NFT economy isn’t without its flaws, but it’s clear that there are very legitimate reasons for malcontents within the mainstream contemporary art world.

ITO: Yeah. I was 26, 27 at the time. I was brand new in the art world and pretty inexperienced and all of the sudden I was selling tons of work, making so much money, constantly getting emails, and everyone wanted to be my friend. Galleries were obsessed with me. And then, yeah, people started selling my work on the secondary market and the prices went extremely high and then the market crashed. Then all those people didn’t give a fuck about me or my art anymore.

I love art, but doing it as a job is complicated. There are certain things I’m willing to do to still be able to do it as a job, but some things less than others. I think all artists struggle with that balance. You want to be in your studio, you want to be making art. But the professional aspects of it can be completely, utterly draining. The contemporary art world can be tiring and hard to navigate and very conservative, which now is not such a secret, but when I first started out it was definitely a shock.

POLLOK: There’s an interesting cognitive dissonance to talking about conservatism in the contemporary art world. Contemporary art museums have a nauseatingly self-righteous perception of their own subversiveness and transgressive social positioning. It’s funny how people who wholeheartedly believe they’re pioneers can be some of the most inflexible institutional gatekeepers. Do you find that since you’ve shifted your focus from projects in the mainstream contemporary art world to NFT projects that public perception of your work has changed? Is the criticism accurate?

ITO: Honestly, I’ve never agreed with any criticism of my work. When I do read it, I feel like it’s always the most basic takeaways. People have been writing the same shit about me for over ten years now, you know? There’s a quote from me when I was younger about the circulation of images or the meaning of reproduction on the internet that’s constantly being thrown around. But, yeah, I’ve always felt that that’s the most basic point of entry for my work. I feel annoyed when people bring it up now because it almost feels like a given. For a long time, I never wanted to have any language associated with my art. I wanted pure art with no kind of contextual information, at all.

POLLOK: Very Lynchian of you, may he rest in peace. Do you know what I’m talking about? He famously refused to elaborate on any of his films because he always said the work speaks for itself.

ITO: I’ve only seen one David Lynch movie.

POLLOK: Eraserhead?

ITO: I watched his Dune. But now I’m realizing I saw the Twin Peaks movie, too, when I was in college. Other than that, I haven’t seen any of his major films.

POLLOK: That’s a very sideways glance at Lynch.

ITO: A lot of my cultural knowledge is like that. I’ve never seen a Harmony Korine film, either. I’ve just seen Kids. I haven’t seen any of the famous movies that people love, like Tarkovsky or Godard. It’s not really my thing.

POLLOK: What else are you watching?

ITO: Really shitty movies. I went on a run recently of, like, movies that are technically thrillers but they’re actually just murder mystery movies from the ‘90s. When I watch a movie, I don’t really want to turn my brain on. I want to turn my brain off. So the dumber the movie is, the more appealing it is to me.

POLLOK: Oh my god, same! I hate art house cinema. I think all day and I don’t want to think more. My favorites are Mad Max: Fury Road and Inception.

ITO: After I saw Nosferatu, my brother gave me this whole take on what the film was about and these different interpretations people were sharing. I was like, wow, people interpret films? That’s so far from what I want to do when I watch a movie. If I’m watching a movie at home or on a plane or something like that, I’ll just read the Wikipedia page while I’m watching because I’m bored.

POLLOK: What else are you doing online these days? Do you still find it a source of inspiration for your art?

ITO: I’ve never been someone who felt inspired or uninspired in regards to making art. I’ve never run out of ideas for making art and I’m constantly excited to make something new. That’s always been a very positive thing for me.

I know I keep bringing it up, but this Gay NFT scene has really been the only artistic place I’ve found community as of late. I felt so, so burnt out on the mainstream art world. Even though I still participate in it to some extent, I feel very on the outside of it now. A lot of the things I used to do, I just don’t do anymore. And a lot of the people that I used to see, I just don’t see anymore. I know a lot of people who are artists, but I don’t have a lot of close friends anymore that I would say I’m in dialogue with about art. With the exception, obviously, of my friends in the Gay NFT scene. What I like about this scene is that everyone’s there because they want to be there and they care about art and that’s the whole thing. There’s no profit motive. There’s no, like, well maybe I’m friends with these people for my job- no social climbing. When you take all this exterior shit away, there’s just people getting totally hyped on some fucking horse PNG, you know? That passion inspires me.

Parker Ito is a contemporary artist based in Los Angeles.

Tess Pollok is a writer and the editor-in-chief of Animal Blood. She is based in New York City and Los Angeles.

← back to features