PERFUME AND PAIN

Anna Dorn

"The book is about a woman on a journey to become who she's meant to be. When [Astrid] finds her signature scent...she becomes stable and solid in her identity."

YASEMIN KOPMAZ: You’re the author of four books, including Exalted, which was an LA Times Book Prize finalist. I wanted to talk about your most recent novel, Perfume and Pain, which was published with Simon & Schuster in May of this year. What drew you to perfume as a theme?

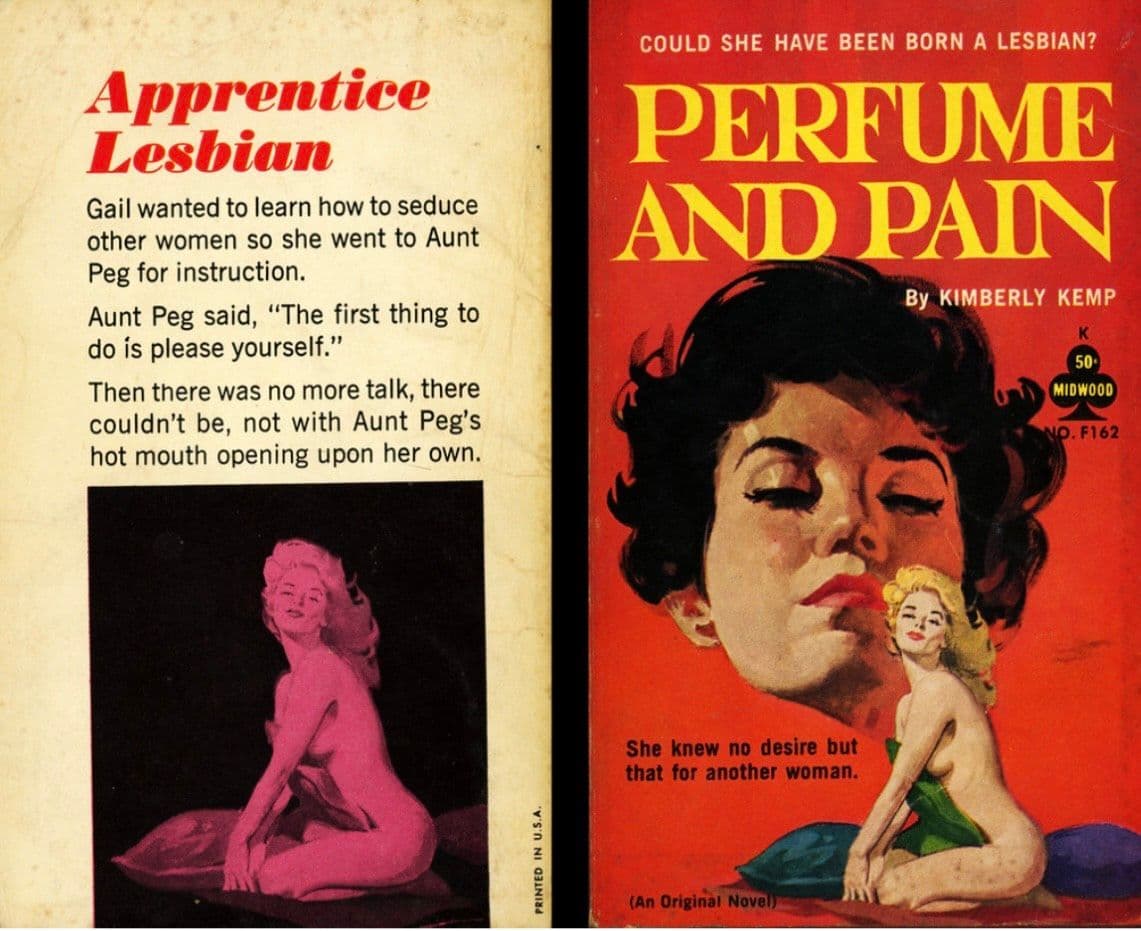

ANNA DORN: When I first started writing the book it had nothing to do with perfume. I got an idea at some point that the main character, Astrid, was going to plagiarize a lesbian pulp novel for her Zoom writing class–a ridiculous sentence, I know–and after I got that idea, I started researching lesbian pulp books. That’s when I came across the original Perfume & Pain, a lesbian pulp novel by Kimberly Kemp. I just knew that was it. I loved the title, I loved the cover, I loved everything about it. So I decided that Astrid was going to plagiarize that novel for her writing class and that I was going to plagiarize the title for my novel.

It wasn’t until the third or fourth draft that I developed a real-life obsession with perfume. I did that on my own time, just for fun. I had this revelation that since I was writing a book called Perfume and Pain, I needed to have a perfume obsession and that knowledge needed to be funneled and collected into the book. But the actual inclusion of perfume as a material plot point was a later draft thing. Perfume obviously fit the themes of the novel–it’s in the title and it’s all about femininity and seduction.

KOPMAZ: What were you thinking about when you developed the Astrid character? What did you want her to go through over the course of the novel?

DORN: There’s actually a paragraph at the beginning of the book where Astrid is talking about how she can’t find a signature scent while collecting her perfume. I saw that as emblematic of her inner struggle. I wanted her to appear scattered and caught between two conflicting drives, the drive to self-destruct and the drive to become healthier and more mature. By the end of the book, she does find a signature scent–which is about her finally knowing who she is and who she wants to be. It’s about her journey to become more stable and solid in her identity as a person and woman.

KOPMAZ: The book has a lot of subtext about queer media, itself being based on a lesbian pulp fiction novel. What conversations about queer representation do you think feel relevant to readers today?

DORN: A lot of queer female media has been really PC lately, PC to the point of being sanitized, boring, and preachy. That was one of the things that drew me to lesbian pulp as a framing device–it’s problematic, it’s sexy, and it’s fun. But, politically, it is kind of horrible. What conversations were you thinking about?

KOPMAZ: I was thinking about The L Word, which doesn’t really have an equivalent on TV today. Although, a lot of Zoomers have told me that it’s aged horribly.

DORN: I’ve heard that too. I’ve done a couple rewatches of the show and I’ve come across things where I’m, like, “Wow, that would definitely not fly today.” But that’s the great thing about the original The L Word–it’s not PC. It doesn’t have a political agenda. It’s more about how women can be hot and glamorous and have sex and be melodramatic and have all these crazy dramatic relationships. It’s a soap opera and I like that about it. I like its unapologetic soapiness.

KOPMAZ: I see that in Perfume and Pain. The romance and relationships are all very dramatic, but it’s not tied to being queer.

DORN: I was recently asked by a different magazine what the first queer novel I saw myself in was, and the one that I picked was Cassandra at the Wedding by Dorothy Baker. She actually wrote lesbian pulp as well, but this one’s more literary fiction. It was written in the ‘60s and the character is a total mess–very Astrid’s type of girl. She’s neurotic, self-destructive, funny, messy, and she’s also gay, which is never explicitly mentioned. Being gay is the least of her problems. I’m drawn to books where being gay is not the soul-defining feature of the characters, and it’s not their primary struggle in life.

I know I speak from a place of privilege with this, but I don’t find that being gay has been much of a struggle for me. I’ve had way harder things that I’ve had to deal with. I suffer in different ways and being gay is just a thing about me.

KOPMAZ: Do you think there’s a punitive instinct to queer circles? I’m thinking about the scene in the book where Ivy writes a callout post about an ex-lover–it felt like you were commenting on cancel culture in the queer community, or hostility and aggressions there.

DORN: I think this is a line in the book, but it’s always the ACAB radical girls who are most desperate to police you. It’s true. There’s this hypocrisy in our culture right now where the person who’s acting the most woke and the most liberal likely ends up being a bit fascistic about policing other people’s speech and actions. I definitely wanted to touch on that with the novel.

KOPMAZ: You also reference the novel/movie Carol in Perfume and Pain. Carol is probably the most visible lesbian story in America; what are your thoughts on Carol?

DORN: I used to be so obsessed with Carol. I thought she was the hottest person ever. I experienced a crazy paradigm shift with that because I was teaching a sapphic literature class with Catapult and we read The Price of Salt and my Zoomer students thought Carol was a complete psycho. That had never even occurred to me before. But I was thinking about it, like, “Woah, maybe they’re right. She is really bad.” I also talked about it with my girlfriend, who’s Gen X, and she was, like, “Carol does suck and is probably going to leave Therese as soon as the book ends.” I just had this revelation that loving Carol is a very millennial trait. What’s the line in the book? “I want her to run me over with a car?” We all think she’s so hot, she’s so cool, she’s so iconic, but we’re completely missing that she’s a horrible person.

KOPMAZ: Do you have any thoughts on male perspectives in writing lesbian characters?

DORN: I’ve heard people say it’s painfully obvious to them that Carol was directed by a gay man and not a woman, so I don’t know. That’s not how I felt watching it. But, then again, I’m partial to a hyper-stylized gay male point of view.

I never realized the original Perfume & Pain was written by a man. It was a little embarrassing; I had to have someone mansplain to me that it was not actually written by a woman.

KOPMAZ: Many of the lesbian pulp novels are written by men, are they not?

DORN: I think a lot of them were, but the ones that have stuck around are the ones written by lesbians. There’s a sub-genre of lesbian pulp called the pro-lesbian pulp, which was written by people like Patricia Highsmith and Patricia’s girlfriend Marijane Meaker, who wrote under the pen name Vin Packer. Dorothy Baker, who wrote Cassandra at the Wedding, also wrote lesbian pulp. So there were definitely a handful of lesbians writing it and reading it. But I think it was predominantly written by men for men, which is where some of the more problematic aspects come from.

KOPMAZ: What value do you think there is in the male perspective?

DORN: There’s a line in the book about how gay men are always telling their friends, “I’m hooking up with this 20-something model,” and lesbians are always telling their friends, “I’m hooking up with this 47-year-old academic.” There’s an ingrained idea among lesbians that they only like a girl because of her intellect or politics. There’s an unwillingness to admit to the libidinal, visual aspects of sex–that’s maybe a refreshing part of the male perspective on these stories, that it highlights that.

Anna Dorn is the author of four novels, including Perfume and Pain.

← back to features