NARRATIVIZATION AND ITS DISCONTENTS

Eugene Kotlyarenko

“I feel an incredible sense of urgency to communicate with people. There’s so much ambient anxiety these days about narrative–like ‘who controls the narrative,’ both personal and cultural. My new work explores how the mediation of reality becomes the ultimate arbiter of the narrative.”

TESS POLLOK: You’re a filmmaker; you made Spree and Wobble Palace, most notably. You’re also editing a new movie right now, which we’ll get into in a bit. I wanted to talk first about your love of the phone and how your work embraces the phone. What’s so poisonous and/or fascinating about the phone?

EUGENE KOTLYARENKO: The immediacy of it. The immediate access to any and every thing, the ultimate library at your fingertips, plus instant access to gratification via human interaction–it’s something that breaks the mind and the soul because human beings didn’t evolve for that. Obviously the smartphone is an advanced state of this, but Marshall McLuhan pointed out something brilliant about our relationship to the traditional telephone: by giving us the ability to instantly communicate with others in a totally disembodied way, it lead to a unique “amputation.” For our entire evolutionary history, immediate communication was reserved for interactions with people who were physically near us. If you were talking to someone you could see them and use cues from their body language to interpret their behavior, and so on–but with the phone you lose the sense of sight, among other things, so in order to compensate for this visual itch not being scratched your mind has to do something else. This is why so many people, when they’re on a phone call, tend to doodle or pace. Because our senses and sense of feedback from the other person has been amputated, we compensate with these other behaviors. Now imagine how a smartphone, which has myriad forms of disembodied communication, takes this amputation to exponential levels.

The other thing is, it becomes a mechanism for reflection without processing. A medium that bounces reality off of you before it can hit your soul. You have these social platforms that incentivize you to turn your life into a collection of completely mediated experiences. There’s no direct social “benefit” to private moments, especially if they’re meaningful or impressive– the rewards of sharing it are always dangling in front of you. So your “life” enters a casually competitive panopticon, placing you into a realm of constant alienation, paranoia and even psychosis. All these aforementioned features: social mediation platforms, a deluge of information and the access to instant gratification, can fast-track a person to hit what I call “digital rock bottom.” To be fair, maybe it’s different for people who grew up with a smartphone, but I have a more transitional experience, as someone who lived before and after its advent. So I inevitably can make comparisons with the “before time” and draw comparisons about what feels different.

POLLOK: How does that translate to filmmaking? How do you see the phone mediating the filmgoing experience?

KOTLYARENKO: Once the phone got a screen, that screen changed our relationship to all screens. Cinema is kind of a screen dream. It’s passive. While on one level, social media is similar to film in that it delivers stories through images and sound over time, the key difference is that we’re much more active participants in social media. The promise is that you are “the main character” living out the central story line. This advanced form of narrative agency is true of general internet use and of course video games, as well. I think cinema is the greatest passive medium– able to represent all other mediums and synthesize how they wash over you. So it gives us a chance to explore and reflect these newer new audio-visual modes without the agency attached to them. When we become observers and voyeurs of our common behavior, we can finally analyze it. This is partly my goal with incorporating these elements into my movies. Of course normalizing active participation in relation to the screen also really affects our habits as “viewers”— so that becomes a huge elephant to contend with. I do try my best to scratch that itch of agency we’ve all become accustomed to, but in a cinematic framework.

POLLOK: It’s an interesting territory of cinema to be investigating because I think we’re in the very early stages of being able to combine these mediums. Like, being on my phone feels exquisite to me–it feels like I’m home. And I’ve never felt that feeling fully communicated to me through film. With Wobble Palace, you incorporated a lot of digital human behavior–but to me these feel like the fumbling first steps towards full communication of the phone experience, like, the pure bliss of being on Twitter while watching a video and reading an article at the same time. You’re one of the pioneers of that feeling.

KOTLYARENKO: Thanks. I think it’s a fine line to walk because I don’t really want people to feel alienated or confused watching my movies. This is one of my greatest challenges as a filmmaker— to make this exploration of the new still feel “cinematic.” The funny thing is, in order to arrive at that feeling, I actually have to be experimental and explore new formal territory. And you can’t predict how people will receive that. Ultimately though, I like the movies to be entertaining, so I try to ground these conceptual ideas in situations and characters that I find to be funny or tense. It’s actually not dissimilar from early cinema, when filmmakers were inventing techniques that didn’t exist yet to most effectively and entertainingly convey their observations and stories. These experiments later became the conventions by which we understand all audiovisual communication. So yeah, I view myself in that spirit of early cinema: experiment to entertain. I think if I was less driven to explore these techniques for laughs or thrills and was, like, a bit more in-your-face boring with them, then maybe the people whose job it is to adjudicate institutional value would be more interested in what I was doing. But when I make those decisions, I only think about what I want to see as an audience member in a theater.

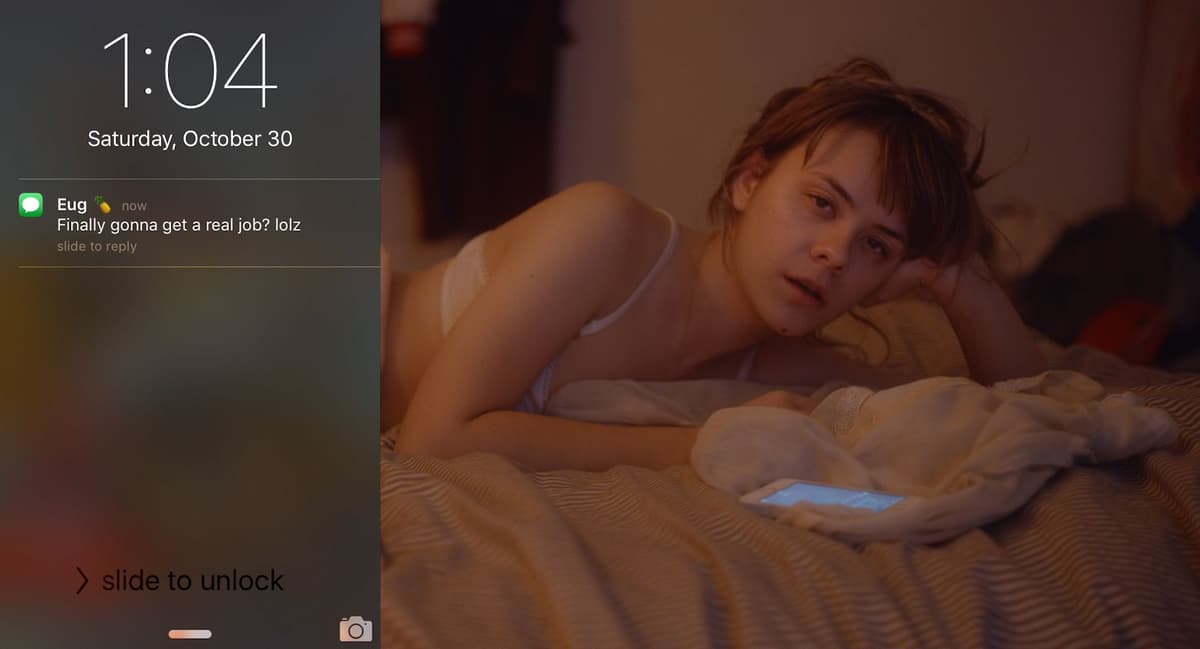

Still from Wobble Palace

POLLOK: Yeah, I’m not a huge cinema head, so I don’t have as great as a grip as you do on what’s going on in that landscape, but I can compare it to my experiences as a writer and novelist–which is that the bigger you bite, the less you can chew. And when you have a very ambitious goal as an artist, the work loses specificity. Like, what I think is really interesting about your work and is kind of a hallmark of your work is the specificity, which maybe speaks to your dissatisfaction with a critical response to work that’s so highly specific. I’d like to live in a world where something being specific isn’t seen as speaking to the skill level involved in its creation. It’s just in the nature of what you’re making.

KOTLYARENKO: What do you mean by specific?

POLLOK: I guess another word could be niche. The attitude I’m critiquing is a critical attitude that because your work is niche, it’s unserious, or somehow not metaphorical. It’s very hyper-real and located in the lives of young people, but that can be a universal experience.

KOTLYARENKO: I think, number one, if something feels honest then it feels universal. If you can create a clear situation for characters and present obstacles, that becomes universal because it’s relatable. That’s the communication from the filmmaker. Also, when you say my films are about creative characters–I think that’s an interesting observation, as well, because we’re in a really funny moment where everyone views themselves as inherently creative because of the nature of social media and how that is a mechanism for sharing content and getting an audience. So every person who has any level of interaction with the world through posting views themselves as a type of creative; it’s not just this elite group of people who are, like, trying to do it professionally. For instance, Spree begins with Kurt Kunkle making a “Draw My Life” video - a simple metaphor for all the complexity and richness of life boiled down to a banal, hyperspeed, two-dimensional piece of art.

POLLOK: Another effect that social media has on the landscape of being an artist is that it’s very atomizing. And you’re right that it erodes the boundaries of what constitutes an artist.

KOTLYARENKO: It’s a shock to everything–to the economy, to family units, to love. It’s shocking that everyone has this responsibility now to publicly leave trace expressions of not only who they are, but who they want to be or what their mind tells them they should be. Like, the idea of leaving traces of your impressions and identity like this used to be reserved for someone who was going to dedicate their life to thinking or art.

POLLOK: For most of human history, art was sort of the private domain of a specific sort of person–someone who had specific intentions and thought a lot about what it was they were trying to do. I think you’re right that the current creative economy makes everyone an artist, to varying degrees.

KOTLYARENKO: Things just used to take longer to make so you had to think more about them. There also used to be more labor required to create things. Now, we’re entering a creative space with very little barriers to entry, which is interesting. The repercussions of what it means to create something have been destabilized. For example, analog cameras–which required the time for photos to develop–were quickly replaced by digital cameras. Just that 30 year evolution changes the nature of what photography means and changes the nature of what every mediated photographic experience is. I’m not saying it makes anything better or worse, just that it makes us different, and we don’t fully know what that destabilization means for normal human interaction.

POLLOK: I think what you’re talking about is also interesting because it ties in with how “esoteric” culture has become really mainstream–like, the average person now is into extremely online subcultures and so on.

KOTLYARENKO: We should also acknowledge in the span of this conversation that a lot of what we’re talking about in terms of the habits of the mind and human behavior is pretty commonplace, so, like, the ability to self-reflect about these habits has also become pretty common. Generally, technology is always ahead of morality and consciousness, and so there are usually stages of catching up, complaining being one of them.

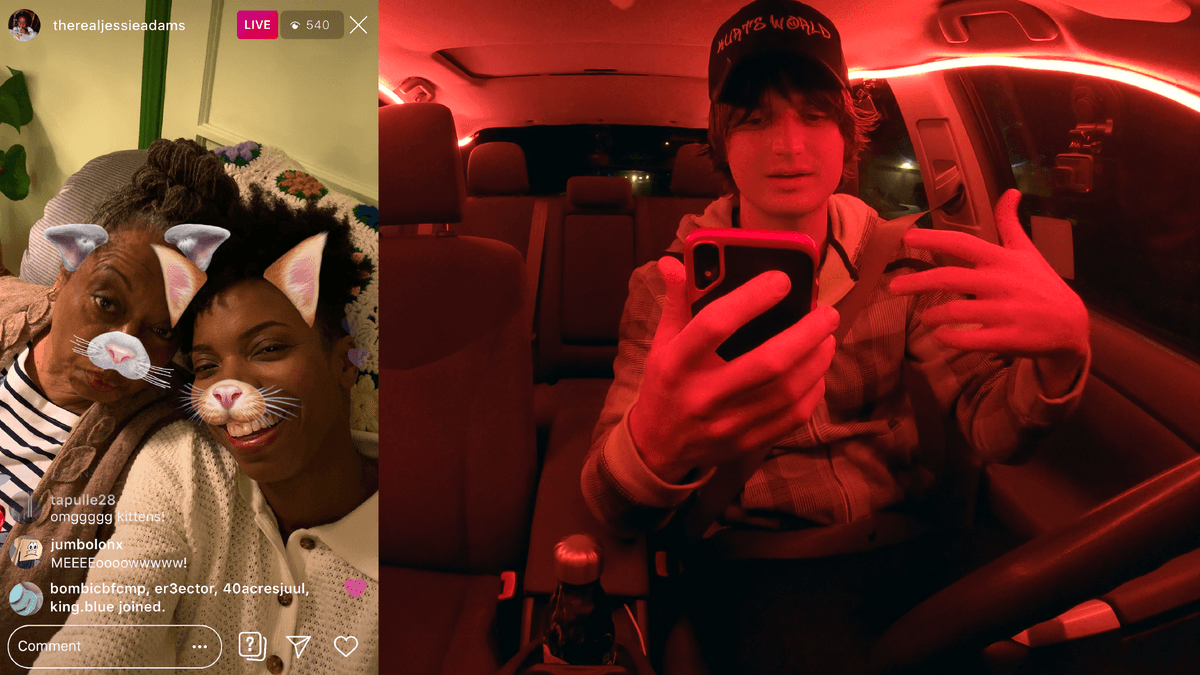

Still from Spree

POLLOK: Who do you think has a perfect life? Or, what is the perfect life?

KOTLYARENKO: This is something I realized in the early days of social media and it honestly helped me. Whenever you’re observing someone in the virtual space, whatever assumption you have about them, moderate it by 2/3rds. So, if someone seems X amount of happy, they’re probably 2/3rds as happy as they seem. If they seem X amount of depressed, they’re probably just 2/3rds as depressed as that. Apply as needed if they’re rich, hot or whatever. If you remember that, the levels of jealousy or inadequacy the platforms are geared to make you feel, go down by approximately 2/3rds.

One artist who I admire is Brad Troemel. Brad found a way to cultivate an audience by pushing his critic-artist practice into an alternative marketplace. I think this has been his impulse for a very long time, at least as far back as when he had a tumblr called the Jogging. I tell this to a lot of my friends who are curators and institutional people–Brad is one of the most meaningful practitioners of institutional critique. You can take issue with whether his observations are always astute or if he’s being edgy, but generally speaking, his critique of the art world works not just via his analyses but by the nature of being directly funded by a receivership that wants the critique. Of course you can get into creator-audience feedback, manipulation and all that but largely what he’s doing is very valuable. Plus I like that he makes trailers and sets release dates. He employs influencer techniques as part of his critique or at least I think it’s part of it.

POLLOK: I watched a lot of his stuff early in the pandemic when I first started Animal Blood and it was a really amazing time for me as an artist. I felt so invigorated by making work and, like, pristine before getting further along with this project–now I care so much about metrics and have so many expectations for the types of interactions I’ll have with other institutions and artists. But, yeah, I associate him with a time in my life that felt very pure, like I was just racing along.

KOTLYARENKO: Kanye is an interesting example in terms of the creative process in the age of social media–he’ll go basically mute for long periods of time and then become hyper-active when he has something he’s ready to share with the world. Many have followed suit. I always think it’s interesting when someone deletes all their posts, goes full tabula rosa for the next phase in life. In general, I think it’s very important for a creative person to have a good balance between creation and consumption. I think all prolific artists find ways to generate as they consume. In a way you inevitably are thinking about how the things you consume relate to your practice and your creativity. I also think that finding moments to reflect on that can be hard. I think not thinking about your work is extremely hard.

POLLOK: I really relate to that point. Sometimes it’s hard to stop thinking because it feels like I’m always thinking, like I’m ripping up my own mind.

KOTLYARENKO: Right now I’m finishing up the edit of my new film, The Code. It’s a very detail-oriented movie and I keep obsessively tweaking it, only to end up with microscopically different results. So yeah, I feel like the mind loves to rip itself up a bit. I did something good for my mind recently, which is that I went to WiSpa. I put my phone in the locker, and then there’s nothing to do except sit and be in the water and get hot. For me it’s the greatest place to think and where I wrote a lot of The Code. I try to get as many ideas in my head as I can remember at a time, and then when I feel like I’m about to lose them, I go up to the common area and write them down. They actually have computers up there, kind of like a public library, and I log in there and write without any of the distractions of my phone or personal computer.

Still from A Wonderful Cloud

POLLOK: Don’t they sometimes beat you at the Korean spa? Like with swatches and leaves?

KOTLYARENKO: If you pay them, yeah.

POLLOK: Do you ever do that?

KOTLYARENKO: No, it’s too pricey for me.

POLLOK: Would you describe yourself as a more process-oriented artist or results-oriented artist?

KOTLYARENKO: I think, like, I don’t need things to turn out exactly how I wanted them to be initially, but once I commit to an image I have of how a film is going to look or be, I become a results-oriented artist. On set or within the formation of the edit, I’m pretty open to everything that’s cool and collaborative about filmmaking, and I think it can be fun to get other perspectives. It’s also challenging, because you do have to balance other people’s enthusiasm and charmed perspectives with your overall vision of the thing. But in general, what I find really exciting about filmmaking is that it makes me feel great about humanity and other people because it’s, like, “Oh, everyone has such good ideas.” You just end up thinking about how deeply you care for the work and how lucky you are to be making the movie and working with everyone that you’re working with. But eventually you do settle on an outcome where you’re, like, “I’m done. I love this.” And after you work so hard to make the “audience-compass” inside yourself happy, you hope it elicits the emotional response you were looking for and the interaction with the film that you are hoping to get from viewers.

POLLOK: Do you have any solutions to the social and behavioral problems caused by technology?

KOTLYARENKO: I’m curious about the problems, but I don’t have solutions. I think my responsibility as an artist is to find compelling, accessible ways of interrogating these questions formally and narratively. Like I’ve said, I think technology is always ahead of people. Whatever the “easiest” development is, will be what’s going to happen. For instance, if the things that make life “easier” for everyone involve technology leading an entire civilization or species to ruin, that’s exactly what will happen because it’s easier, you know? But to that point, it’s difficult to speculate on the repercussions of these things, because in the moment all we can see is how inventing the wheel is easier than walking.

The main anxiety that people have now, which they’ve had in sci-fi circles since the 50s and probably much longer, is that a form of technology will develop consciousness or have desires or selfishness of its own. What would that mean for the future of humanity? We just don’t know where this is all going or what the effects of these things will be. So I just do my part in observing–I see things happen where I think, “Oh, that’s funny,” or “Oh, that’s sad,” and I observe my friends –that’s basically where my set of creative instincts come from.

Right now, I’m writing a movie about my childhood in Brighton Beach, and I think it would be a great movie, but I’m having to constantly convince myself of the urgency of it. Making a movie about my childhood in the 1990s obviously feels personal to me, but it just doesn’t feel urgent. When I deal with contemporary life, I feel a terrible level of urgency to communicate with people. When I make a movie like Spree that’s about the desire for virality and the violence shortcut, that feels urgent. Or my new one, The Code, which is about a couple surveilling each other because they’re afraid the other person will cancel them–that feels relevant and funny to me. There’s so much anxiety these days about who controls the narrative and our relationship to narratives, both personal and cultural. How do we view events in the moment and also retrospectively? What is an accurate representation of reality within a universe where everyone “main-characters” their own experiences? I thought a film in which the characters surveille each other and edit that footage, would make for an urgent, compelling viewing experience that explores these questions of “Who controls the narrative?” Hey who knows, maybe the film will offer people a few fun solutions to their modern problems.

Eugene Kotlyarenko is a filmmaker based in Los Angeles, California. He has directed 6 feature films, including Spree and Wobble Palace. His 7th film, The Code, is set to premiere this summer.

Tess Pollok is a writer and the editor-in-chief of Animal Blood.

← back to features