MENTAL HELLTH

P.E. Moskowitz

The way we think about mental health obviously isn’t working because everyone is depressed and suicidal and anxious and lonely. Mental Hellth is about having a different conversation and pointing out where or how our thinking might improve.

TESS POLLOK: You’re a writer and the editor of Mental Hellth, a Substack on mental health under late capitalism–I’m a huge fan of Mental Hellth, by the way, I was definitely one of your first subscribers. I remember when there were only three or four articles up. My favorite then, which is still my favorite now, is “Drugs Are Just Drugs,” in which drug policy journalist Zachary Siegel talks about differences in how SSRIs are prescribed vs. how suboxone is prescribed for opiate withdrawal; it changed how I think about prescriptions. What would you say the thesis of Mental Hellth is?

P.E. MOSKOWITZ: To speak to your point with the article, drugs really are just drugs and whether they are prescribed or not they can be helpful or harmful. We often have this false dichotomy between prescribed drugs and non-prescribed drugs as if they’re not all just mind-altering chemicals. But I would say that article points to the overarching thesis of Mental Hellth, which is that the way in which we think about our brains and about what’s good and bad for them is completely wrong. We have a singular narrative about mental health being handed down to us on high from the practitioners of mental health, the pharmacological industry, and our political system and it’s all reinforcing this belief that mental health is something highly individualized and we’re supposed to deal with it on our own. I just felt like there was something in that mindset that needed challenging. Obviously, the way we think about mental health right now is not working because everyone is depressed and suicidal and anxious and lonely. Mental Hellth is about having a different conversation and pointing out where or how our thinking might thinking might change or improve.

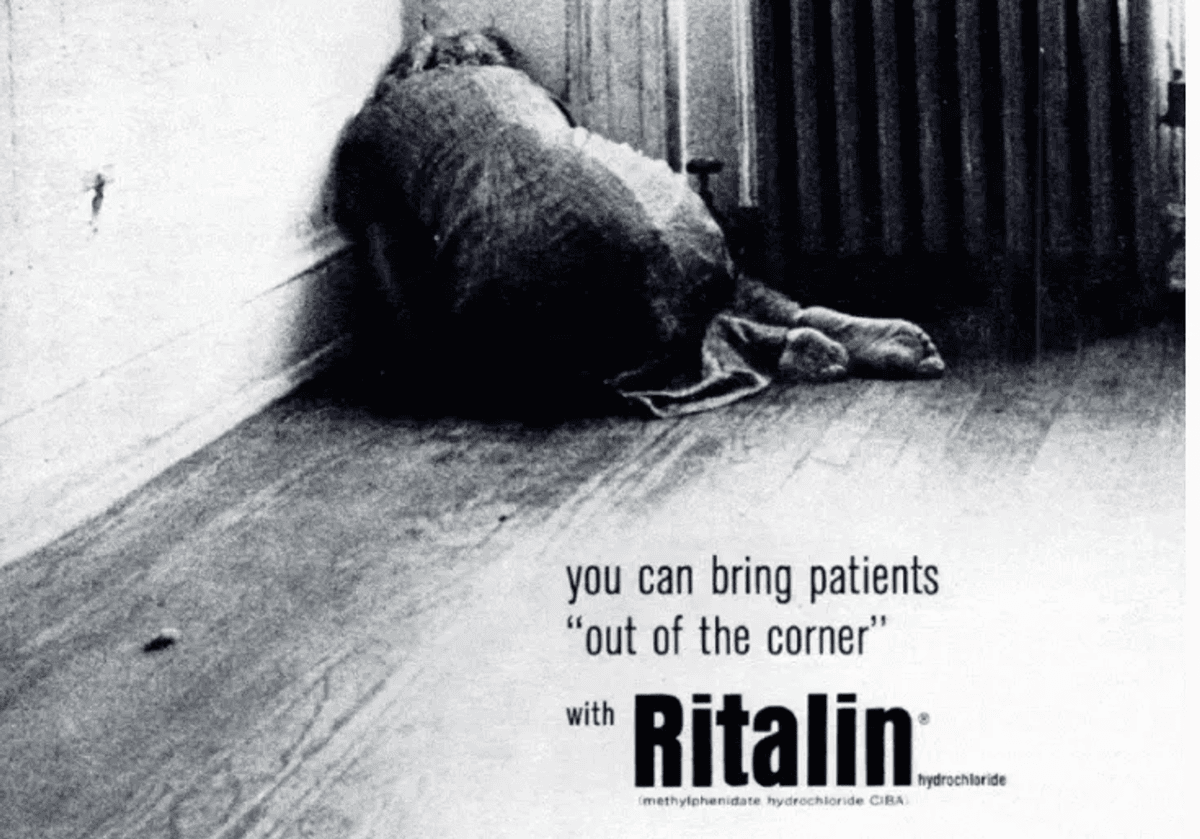

POLLOK: Your most recent piece for Pioneer Works, “The Repression Pill,” was part of a series of dispatches on the Adderall epidemic. I was just wondering what you think of Adderall and of the Adderall shortage, generally, since you’ve written so extensively about the effect Adderall has had on people’s lives. Personally, I’m an Adderall user and I take it a lot, it’s one of the only things that’s ever helped with my treatment-resistant depression.

MOSKOWITZ: Uppers increase the amount of dopamine available in your brain whether that upper is speed or meth or Adderall. It’s not surprising to me that Adderall would be very popular these days when we lead these very bleak, depressing, isolated lives where we’re all tied to a computer screen for ten hours a day. Does that mean Adderall is bad? No, but it means it’s part and parcel of this system by which we don’t have enough naturally occurring dopamine in our bodies from our lived experiences. I like Adderall and I take Adderall, as I mentioned in that piece, three or four times a week. I feel similarly that it helps me feel less depressed and has worked better for me than any SSRI ever has. But I kind of wish we lived in a world where that wasn’t necessary, I guess. But when I give criticism of these tools we use to cope, like prescription drugs, I’m not saying that they’re bad, I’m just saying that, ideally, we would live in a world where these tools weren’t necessary.

POLLOK: What do you think are some productive changes that could be made to society to make people less reliant on drugs?

MOSKOWITZ: I mean, abolishing capitalism is too trite of an answer, isn’t it? [Laughs] What does that even mean at this point? But the ability to live lives that are based in bodily autonomy is a huge factor. I think deep down a lot of problems with anxiety and depression are caused by a lack of connection to other people or being isolated. So a big part of fixing that is giving us access to lives where we can live in our bodies as we wish, you know, to have fun and have sex and have access to excitement instead of being chained to a cash register or a computer for 12 hours a day. Instead of those things, we kind of have insufficient replacements for them, you know, drugs that give us serotonin are assets that replace exercise, sex, connection…I think in a world where people had the autonomy to enact their bodily and mental needs, we wouldn’t need so many drugs to feel better.

POLLOK: That makes sense. Raising the minimum wage also comes up a lot. I think it would address a lot of historical and political ills.

MOSKOWITZ: Totally. Raising the minimum wage, lowering rent–that would be a huge one, I think any time we look back at history and at these cultural and artistic moments that we admire, for example New York in the ‘70s or ‘80s, it’s always because these were considered places of pleasure and culture. What’s underlying so many of these cultural bubbles is an economic system where you’re paying a quarter of the rent that we’re expected to pay now.

POLLOK: I have a big question for you, and maybe it’s too broad. I wanted to ask you about the trauma-industrial complex. People these days seem obsessed with trauma, which obviously plays a huge role in how we treat mental health. I just feel like our entire culture has become trauma-brained, it’s become a lucrative venture for a lot of commercial art to exploit trauma narratives, etc. Right now, the most popular narratives in movies and books are all trauma-driven, or they’re about overcoming trauma. But people’s fetish for it just seems to be making things worse, in my opinion. What’s your take?

MOSKOWITZ: Yeah. There are so many things to say to that. One thing is that trauma gives us a feeling of identity and agency, especially in the online world. It gives us the authority to make truth statements, like, “I believe this thing, and this thing is correct, and you can’t challenge me because it’s based in a personal history of trauma or transphobia or whatever.” That kind of ends all debate and argumentation about that thing. Trauma and the trauma narrative have become very attractive for that reason. But I also think that we’re addicted to the narrative of personal trauma because it allows us to ignore all of these societal factors that are making us feel depressed all the time. It gives us the illusion that we’re in control of things. If you live in a shitty world that’s making you depressed and everything about it is making you depressed–then, suddenly, you believe it’s because you’re personally traumatized and you can fix that with therapy or with body work, or whatever, you’re basically putting the locus of control within yourself as opposed to this much larger system. It’s a false promise of control that’s very attractive in a world where we feel increasingly out of control. But it’s very bad and scary in that it distracts us from larger social histories and problems. That being said, you can hold two truths in your head at once. I think that many people are traumatized by our exploitative governmental system, generally, and are also traumatized, acutely, by incidents that have specifically happened to them. I’ve done therapy, I’ve done body work, and those things can definitely be helpful. I have an exercise routine that completely keeps me alive. But if we only use individualizing narratives, and trauma is one of the most individualizing narratives that we have, we can miss the forest for the trees, so to speak, and don’t see how we’re all connected to each other and how we’re all being affected by the same things. To use a metaphor, imagine we all live next to a huge factory that’s spewing toxic waste everywhere. The toxic waste gives me lung cancer, it gives you bone cancer, it gives someone else asthma, and so on. Then we all decide that the thing that needs addressing is whatever we specifically have–so I’m shouting about lung cancer, you’re crying about bone cancer, we’re all looking for these different cures. By only focusing on what’s happening to the individual, we’re ignoring the fact that there’s a giant factory down the street that’s making everyone sick. That’s how I feel about trauma.

POLLOK: What conditions under capitalism make our mental health worse?

MOSKOWITZ: I think social disconnection writ large is a huge issue. A lot of these issues are tied to work and to rent. If you have to pay more than half your income in rent each month, you’re going to be working a lot, which means you have less time to hang out and see people. The underlying theme that people rarely discuss is that we’re all so lonely and isolated that it’s driving us fucking insane. If you venture into different mainstream media channels, it seems like everyone is insane–because everyone is insane, because that’s what happens when you’re, like, basically locked in a padded cell for years on end. That’s basically what’s been done to us. Antidepressant prescriptions have skyrocketed year after year and everyone’s in therapy these days or doing yoga. But if those things were the solution to our problems, we would expect to see rates of depression and suicidality going down. They just keep going up. That’s what’s undiscussed, in my opinion, is that we’re living lives of disconnection and isolation that make us hate ourselves and each other.

POLLOK: Yeah, I also think there’s a connection here between that thinking and how social justice now hinges on the axis of everyone’s personal trauma and no one is interested in the greater good anymore.

MOSKOWITZ: Right. I’ve written about this before, actually, but I think a lot of social justice these days–and to be clear, there are a lot of people doing actual good work to materially change things–but a lot of social justice culture and language these days is just a new form of white puritanical elite culture, this idea that if you have the correct way of thinking about things then that will somehow change the world. What that actually does is isolate everyone who doesn’t have access to the quote unquote right way of thinking about the world and ignores their material circumstances in favor of, like, a morality-based society. Not to be conspiratorial, but I feel like it’s a psyop–not necessarily from the government, but that we’re enacting against each other–to ignore the material conditions of the world and any possibility of material change in favor of, like, right think. Again, that’s something that people feel is easier to control, rather than ask themselves what they can do to stop half the country from dying of overdoses.

POLLOK: To what extent do you think mental illness is neurochemically or biologically rooted in the brain? You write a lot about how socialization processes impact our mental health, but I’m interested in your beliefs on the science.

MOSKOWITZ: I think we all have genetic differences in our brains and the extent to which those differences are helpful or harmful depends on our society. Like, any mental difference could potentially be judged to be as serious as schizophrenia, depending on social factors. I just think it’s all contextual. Yes, brain differences exist. But whether those things are categorized as disorders or disabilities is based on whether society deems them maladaptive or not, essentially.

POLLOK: That’s a very Darwinian answer. That’s kind of how Darwin came up with the theory of evolution, studying the beaks of different finches and judging based on how good they were at cracking open seeds.

MOSKOWITZ: I mean, isn’t society kind of structured in a eugenicist sort of way where we’ve decided that there’s one normative mode of everything that we all strive towards? I think in a more just society, things like schizophrenia, or even less extreme things like ADHD or autism, wouldn’t be deemed as being in need of correction. They would just be differences that are value neutral.

POLLOK: Have you read Tao Lin’s article in Mars Review of Books, “The Story of Autism: How We Got Here, How We Heal?” I’m curious what you think of it. He has a different perspective than you; he thinks rates of autism are linked to dangerous chemicals in our environments and that autism should be cured.

MOSKOWITZ: I think we don’t know enough. I know that’s an annoying answer, but there’s a dichotomy between pretending that everything is completely innate, which is what a lot of mental health advocates go for, and then saying you have autism, you have ADHD, full stop. Or, there’s a more adaptable narrative that is sometimes peddled by the right that if you just eat better and exercise, you can change everything in your life. The truth is somewhere beyond all of these things. The truth encompasses all of these things and more. Yes, environmental factors are affecting our mental health–microplastics have broken the blood-brain barrier and all that. I think more research needs to be done into how the chemicals in our food affect our mental health, because how could they not? The only thing I’m actually against is, again, the individualistic conception of mental health as something that you can fix on your own. Going back to the factory metaphor, you can only do so much to adapt your brain to a sick society. You have to eventually work on that society if you want to actually see society-wide results.

POLLOK: Have you had experiences with your own mental health that made you want to write about these topics?

MOSKOWITZ: Oh, yeah, well, my parents are both psychoanalysts. So I’ve been primed since day one to be thinking about this stuff. Seven years ago I had a nervous breakdown, or psychotic break, after a near-death experience and basically just lost my marbles. You know, waking up every day with insane panic attacks and wanting to kill myself. It was not a good time. I think that’s what pushed me into thinking through these topics more deeply. The narratives that were offered to me about how to think about mental health were not helping me, personally, so I wanted to explore other narratives. That’s how Mental Hellth began, really.

P. E. Moskowitz is a writer and the editor of the Substack Mental Hellth.

Tess Pollok is a writer and the editor-in-chief of Animal Blood.

← back to features