FOLK HORROR AND THE AMERICAN OBSESSION

Maggie Dunlap

Some people have this idea of me as a callous edgelord, when really I’m just…working through my relationship to death in a way that’s not unique to me. I think there’s something to be said for being able to scare oneself.

LILY SPERRY: Maggie, hi! I’m lucky to have caught your two most recent shows—“Gilded Splinters” at No Gallery, and “Very Friendly,” the group show curated by Agnes Gryczkowska at HOUSE Berlin. You also did an international move from London to New York around that time. How’s it being back?

MAGGIE DUNLAP: It feels great. For all its faults, of which there are many, New York is a very warm city. It's interesting because I didn't feel like living in London was influencing my work while I was there, but once I moved back and started making the work for the No Gallery show, I saw so much of an influence—not just of London, but of England in general–on my work.

SPERRY: How so?

DUNLAP: Folk horror films have always been a huge inspiration to me, but it never really popped up in my work until I had my own experiences in the places where these stories come from. My boyfriend is from the southwest of England, like, Plymouth, Devon, Cornwall area, which is a really pagan place with a lot of folklore that you can feel bubbling right under the surface. He shared a lot of the folk tales that he grew up with, and hearing these sort of cryptic ghost stories, when you're actually in the middle of, like, a stone circle, was definitely a really special experience. That's an experience I'd like to try and replicate in my work.

SPERRY: I can definitely see those influences in your work.

DUNLAP: Once I got some distance from England, I was able to really appreciate and synthesize all that I had absorbed over my four years of living there and make something out of it. I think that having a little bit of distance from something, literally and figuratively, is really important in making something interesting. I probably wouldn’t have made that specific type of work had I not moved away.

SPERRY: It's always funny to be in Europe, or places that generally have so much more history. America as we know it is so new.

DUNLAP: And to see the ways in which people live amongst ancient ruins, how seamlessly integrated that is into their daily life… It's such a different sort of perspective on time to be in a place that is just so much older. It changes the way you think about the scope of history.

SPERRY: How were you first exposed to this sort of subject matter?

DUNLAP: I was fully immersed in horror growing up—and I still am, in many ways—but I was lucky in that I had an organic way of coming to those things being a very curious kid on the internet. I didn't necessarily go searching for gore and violence, but I was really obsessed with learning about haunted houses, both real and "fake"—like animatronic, Universal Studios Halloween Horror Nights-type things. So I spent a lot of time clicking around on old Halloween haunted house manufacturer's websites, or reading ghost stories or UFO stories on green text/black background-style websites.

SPERRY: Classic.

DUNLAP: No one shared this kind of stuff with me and it wasn't a part of my parents’ visual language. I just was so obsessed that I would seek these things out. And that habit, for lack of a better word, of having a laser focus on something and then seeking it out at all costs, is kind of the way that I think about my practice. There's a really strong research component.

SPERRY: You’ve referred to your practice as being obsession-driven.

DUNLAP: I just interviewed Brad Phillips for Snuff Magazine and we were talking about obsession a bit. He quoted Stephen King, who said in On Writing that artists are lucky to have maybe one or two things that they're very obsessed with, and they just have to follow that at all costs. And I really do think that's true. The older I get, the more I'm like, Okay, even though these different facets of my practice may look different, they are ultimately all driven by the same obsession.

SPERRY: Do you think that’s built into the artistic personality?

DUNLAP: Probably.

SPERRY: What's your usual timeline with your pieces? How much time is spent on research versus, say, execution?

DUNLAP: I would say that the sculptural part of my practice is more straightforward. Sculptures I can conceptualize and then fabricate within a month of coming up with the idea. The research, though, is never-ending. I couldn't put my finger on a beginning or an end because it’s just so integrated into my life and my process.

SPERRY: Have you always approached your work in this way? When did you first get into digital art?

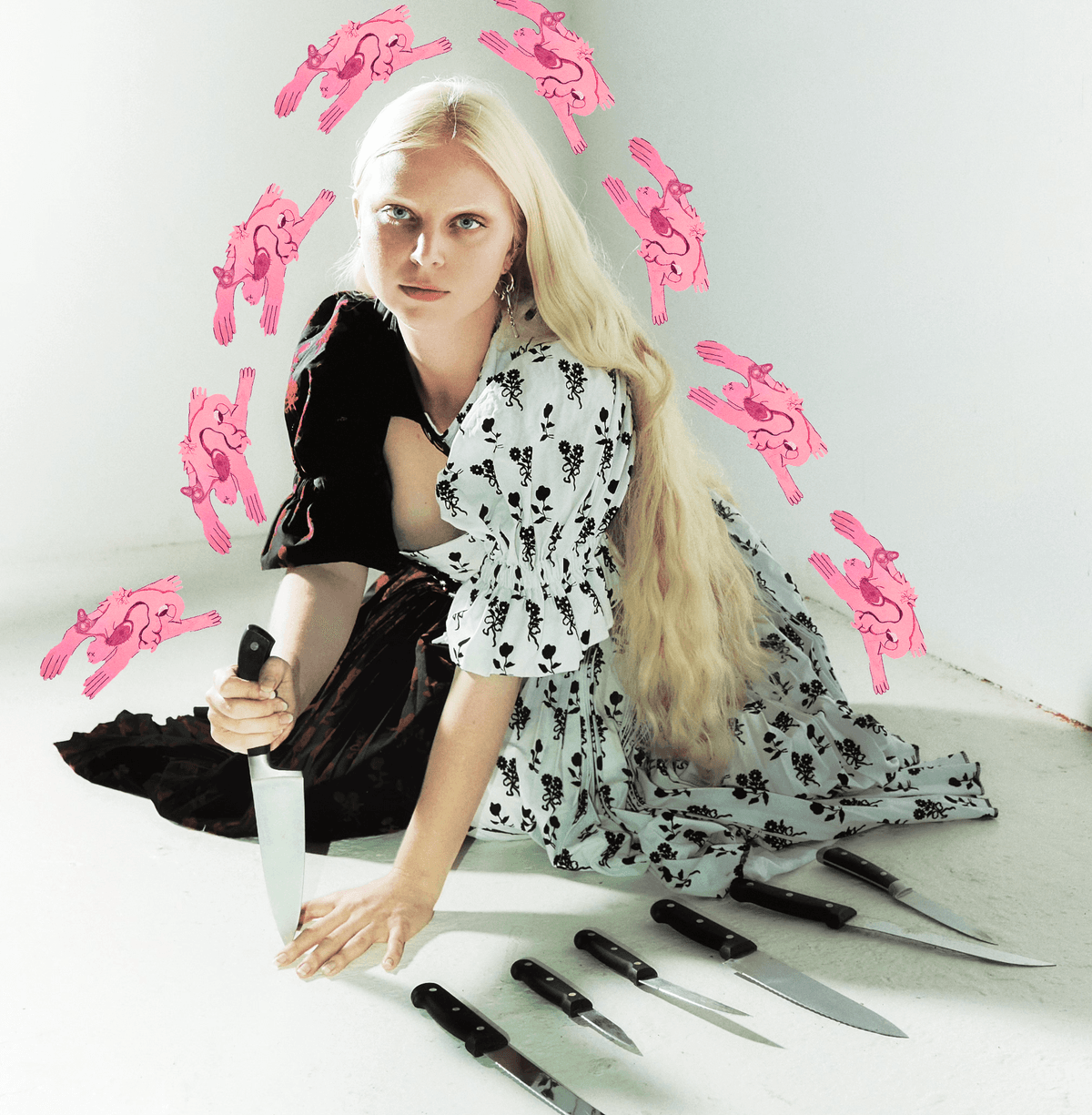

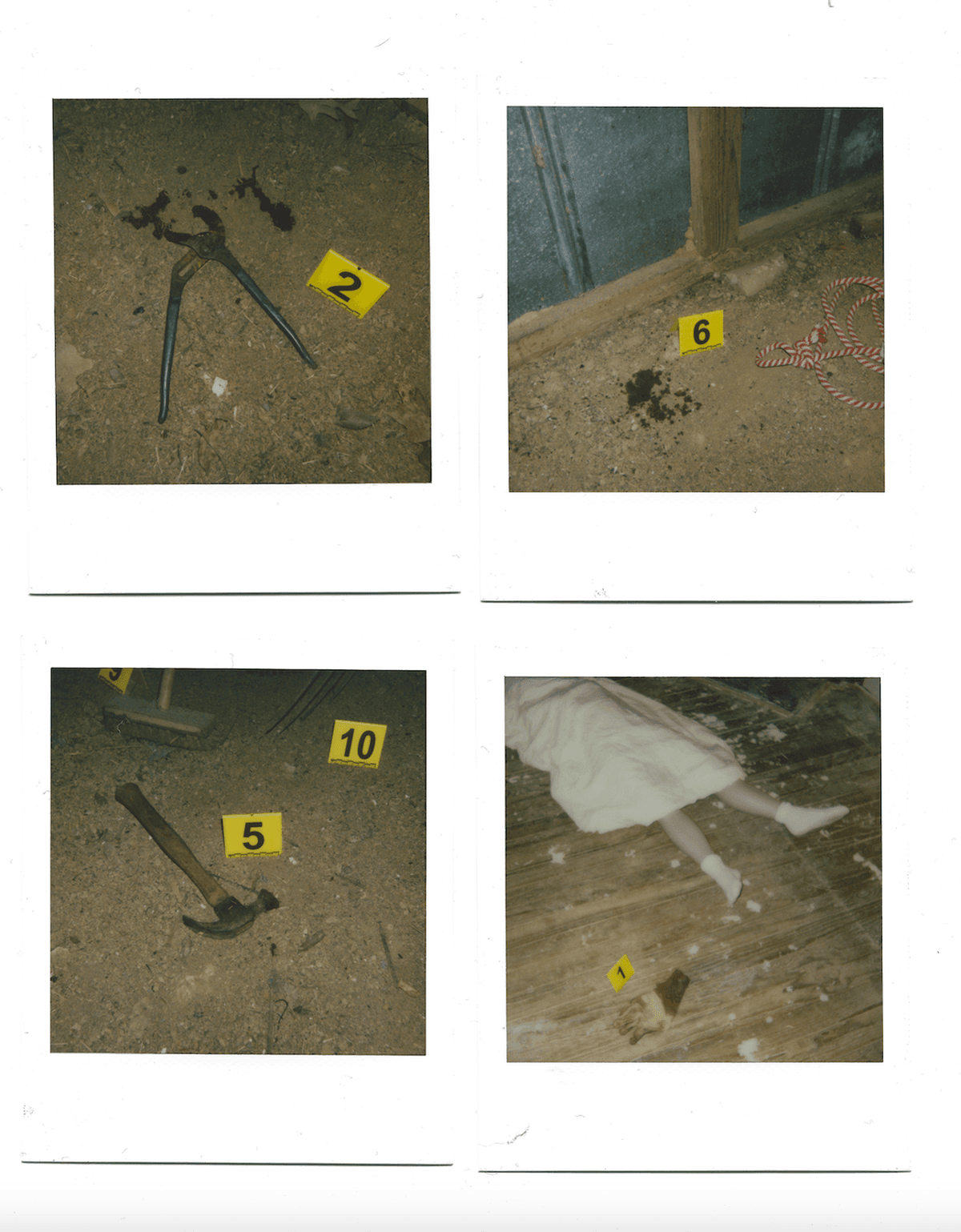

DUNLAP: The real foundation of my practice is in drawing and installation, and that's what I focused on when I was in undergrad at the School of Visual Arts. When I went to the Royal Academy of Arts in London, I had every intention of continuing that and expanding further into sculpture, but I went at the time of Covid, so everything shut down two months into attending. I didn't have access to resources, space—anything. That's when I started to really think about the internet as a site for performance and changed my practice to be more digital. I really wanted to make things that lived online that were more than just a documentation of something I'd made in real life and then uploaded to the Internet. So I started doing the True Crime project, where I made my own snuff images and films and crime scene photos, and I "leaked" them on Reddit with a fake narrative. They became pretty widely circulated on certain subreddits and weird, dark threads. And that was a project totally fueled by my own obsession with true crime and the way that people interact with those types of images and types of stories. I wanted to figure out a way to experiment with that, or use the captive audience of other people who were just as obsessed with true crime as I was—and still am, even more so—in an art context.

SPERRY: I feel like the true crime audience can be very fanatical. They’re probably more invested than your average art crowd.

DUNLAP: Exactly, they’re sort of primed to interact; they want to solve mysteries, they want to be right. And everyone really believed them to be real, which I didn't expect. Only one person was like, "Whoa, everyone calm down. This might be an art piece." [Laughs] It's a great audience to use as sort of actors in an online play. ****That project is still ongoing, even though I’ve shown the work. I find that it has a life of its own.

SPERRY: Are all of the images and videos of you?

DUNLAP: Completely, yeah. I didn’t feel comfortable asking anyone else to do that—to get naked and look dead—so I just taught myself special effects makeup and did it myself. And because I was leaking them, there are no identifying features; my head, my hair, my face… none of that's in it. I really was just a nude female body. I do think it had a bit of a psychological effect on me. I would actually scare myself somewhat, which can be fun–I think there's something to be said for scaring oneself. My boyfriend and I would go out into the forest and he’d be like, “God, I hate seeing you like this. Like it's actually really gross.” [Laughs] And it did feel gross. To embody a corpse is not something that I enjoy doing all the time.

SPERRY: This is maybe an obvious question, but what’s your relationship like to death? Was that a preoccupation of yours when you were younger?

DUNLAP: I don't really know what my relationship with death is yet. I feel like that’s not unique to me. In a way, I think I’m doing some shadow work in my art practice—not necessarily with the goal of making peace with death or understanding it, but that kind of is a side effect of making the work that I make. A lot of my work is trying to tease out how I feel about certain things that a lot of people seem to have definite answers to. True crime is actually a good example of that because, as a genre, it’s something that courts a lot of disdain and rightful critique from some types of people, and then a lot of steadfast defense from others. And even though I enjoy a lot of that media, I was never really sure how to feel about it. There's something darker at play, not in a pejorative sense, but something that is not being fully investigated. The preoccupation with these things... There isn't an easy answer to that question.

SPERRY: I imagine that it's comforting for people to have this sort of container for the death and horror that they’re confronted with on a daily basis. You can opt in and then opt out.

DUNLAP: Exactly. It fits into a way of thinking about time and lives as things that are very linear—bad guys, good guys, an overarching narrative. A true crime documentary will wrap things up and end on a light note when that just doesn't exist in real life.

SPERRY: Do you have any memories of serial killers from when you were growing up?

DUNLAP: I was at school at the time of the DC sniper, which is actually a really formative memory for me—being kept home because the sniper was targeting kids getting off school buses. But the stories that I ended up becoming fascinated with were the ones that captured the country's imagination—John Wayne Gacy, Ted Bundy, Jeffrey Dahmer.

SPERRY: It’s funny, my aunt is convinced that John Wayne Gacy stopped by her house in the Chicago suburbs because he saw a basketball net outside. She just thought he was a repairman and let him in.

DUNLAP: Holy shit.

SPERRY: She said he looked around, didn’t see any boys, and left.

DUNLAP: He was like, There's nothing for me here. Wow, that's crazy.

SPERRY: Were you ever into Ted Kaczynski? He has a very devoted fanbase. There's this narrative of him being just kind of misunderstood, or not in the wrong necessarily.

DUNLAP: Yes, of course. He had a manifesto. And he actually walked the walk, which is pretty rare, actually. A lot of people are all talk but don't actually send bombs to people's houses.

SPERRY: It’s interesting to think about all of these things. I tend to avoid it.

DUNLAP: Making “True Crime” had an actual effect on me, spiritually and emotionally. It did bum me the fuck out. Sometimes I think people have an idea of me as a callous edgelord, when I am really just trying to figure out how I feel about these topics. I don't believe that anything is off limits because it's uncomfortable or difficult to look at, but when I spend a lot of time making that art, I have to take a real conscious breather.

SPERRY: Is it a boundary thing?

DUNLAP: It's more like a tolerance break, where I have to not look at pictures of dead bodies every day for a little while, or not make those images of myself. I try to seek out the other things that I am equally as obsessed with instead.

SPERRY: Like what?

DUNLAP: Folk tales, ghosts… Anything that touches on the way in which spaces can hold onto memory. I'm making a lot of work now about how objects and places can become charged by the things that have happened there — so basically, that just means haunting. But that is the kind of stuff that I can immerse myself in without it having a profoundly depressing effect on me. To read classic English ghost stories, or even theory about memory and hauntology… Those are the obsessions that don't bum me out after spending a lot of time in those worlds.

Maggie Dunlap is an artist and writer based in New York. Following her inaugural New York solo show at No Gallery earlier this year, she’s currently working on a book.

Lily Sperry is a writer based in New York. Alongside various freelance projects, she edits fiction at Expat Press and runs a weekly health newsletter, Health Gossip.

← back to features