FICTION TECHNOLOGY

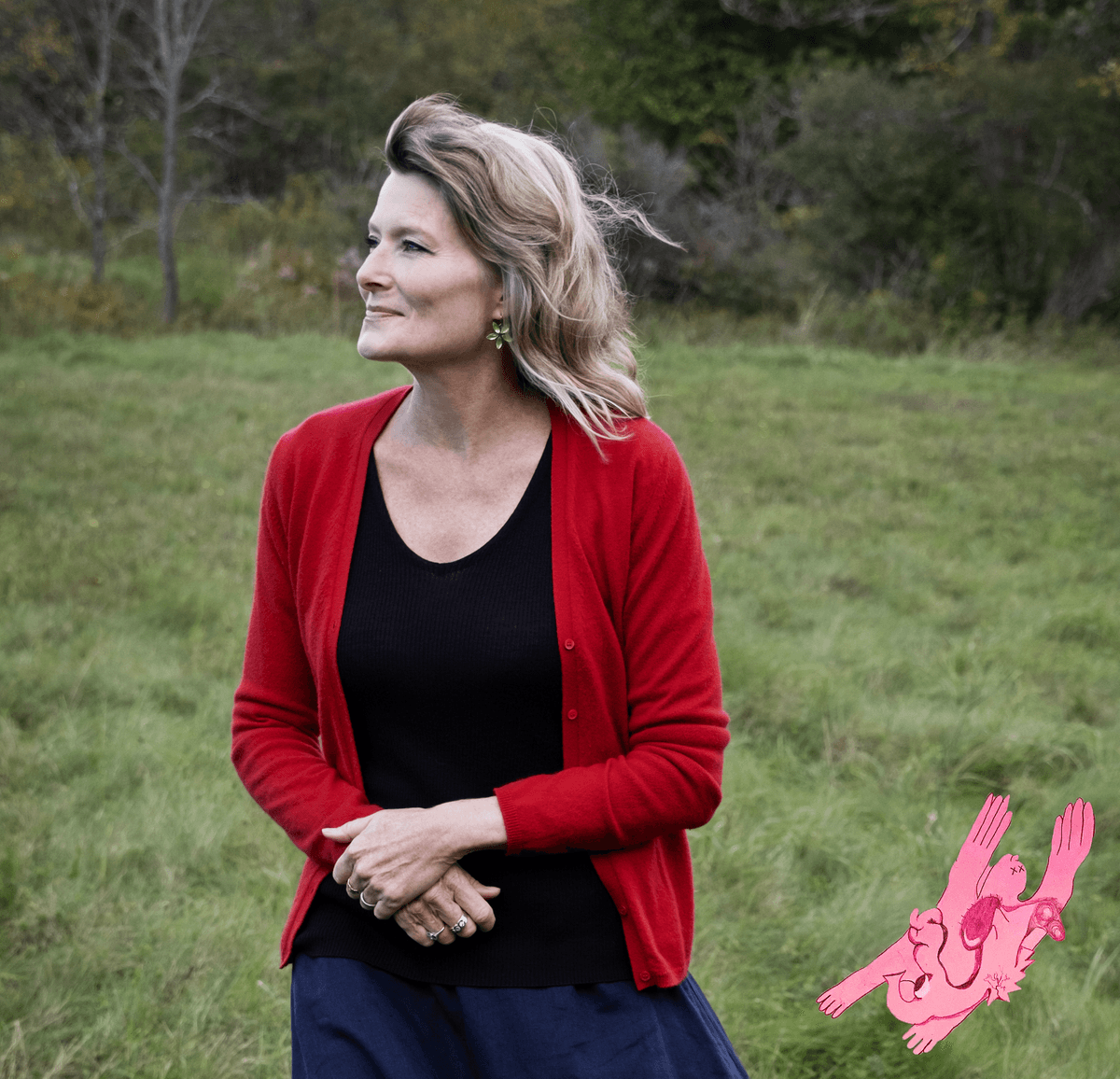

Jennifer Egan

The more we can insist upon the relevance and centrality of literature to deep thought, and the relevance of analytical skills in our roles at citizens and voters and people, the more this kind of coursework– whether it's philosophy or history, any of the humanities– will be acknowledged and understood.

JOHANNA STONE: I wanted to start by asking what you're currently reading and writing. In a recent interview you mentioned starting a 1950s crime novel. Is that your main project right now?

JENNIFER EGAN: That's my project. I was working on another first draft at the same time for quite a while. That one takes place in New York both in the present day and the 1870s, but I stopped working on that to just focus completely on this crime novel. I had a notion of finishing it by the end of the year, I think there's no way that's going to happen, but hopefully not too long after. And as often happens, what I'm working on really dictates my reading, not just because I need to research things, but because my appetite is really for certain books that I sense will feed my project, which means that I've read an incredible number of crime novels in the last few years, which has been really fun.

I'm actually reading another book that's unrelated but worth mentioning because I just think it's so good... It's called The Wisdom of Finance, by a professor named Mihir Desai who teaches at Harvard Business School. He uses works of literature from different eras and parts of the world to illuminate some of the basic notions that underpin finance– I'm one of these people who just turns off at the mention of the word finance. I don't know what it is, my brain just does not want to absorb it. But what I realized from reading this book is that I actually I think very much in terms of some notions of finance, creatively. When I think about making creative choices, I think of it very much as a kind of cost-benefit question. For example, if you write in first-person, what you're gaining is a tremendous amount of intimacy– we're deeply inside a point of view. What the reader is losing is every other point of view, so it's very limiting in that way. And the question is; are we gaining in intimacy enough to compensate for the loss of all that variety? And therefore a book that's written in the first person but doesn't really feel intimate– where we haven't really gotten deeply inside the habits of thought and habits of mind of that person– can be not that interesting. So I think about those choices all the time and I realize that that's actually the same kind of thinking that underpins basic financial theory. One of my favorite writers is Edith Wharton and I found myself thinking about how her work really lends itself to a kind of financial analysis, especially The House of Mirth, one of my favorite books of all time, which is a tragedy, and the tragedy comes about in large part because the protagonist is not able to make a financial choice about her future. And making no choice is a choice.

STONE: That’s a really interesting lens to think about literature. How did you come across The Wisdom of Finance?

EGAN: The author is interested in creating a course at Harvard that combines finance and literature, and he reached out to me about it, and that’s something I’m also interested in. I’ve taught at Penn a couple of times and felt concerned about how many undergrads are business majors for reasons that seem unclear even to them! Their parents want them to. And so obviously that choice in and of itself is a business decision. The parents are thinking; We are paying a fortune for this education, going into debt potentially. We need to make sure there's a return on that investment and we don't believe that a humanities major will give us that return, or will give our child that return. And I think that that is false information. So when Professor Desai approached me, I thought, yeah, I'm really interested in talking about this because I think the more we can insist upon the relevance and centrality of literature to deep thought, and the relevance of analytical skills in our roles at citizens and voters and people, the more this kind of coursework– whether it's philosophy or history, any of the humanities– the more the relevance of those areas of study will be acknowledged and understood.

STONE: You’ve said in previous interviews that you’re smarter when you’re writing.

EGAN: I know writing makes me smarter. I don't want to universalize my own experience, but I do know that there's a kind of intellectual liberation that can come about through writing. I mean, if I hear one more word about AI, my head is gonna explode. I'm so tired of it. I've never even used it, except when it tries to write my emails for me– badly.

STONE: Okay, crossing off my question about ChatGPT.

EGAN: [Laughs] I mean, I'm not opposed. But as far as I can tell, it's full of bad ideas, wrong information, and the kind of writing I'm always trying so hard to get away from, which is groupthink. I mean it is literally groupthink. I'm not interested in groupthink. My goal is to be away from that. So finding some portal into more groupthink... That’s the last thing I’m looking for!

STONE: In your latest book, The Candy House, you write about the concept of groupthink a lot, in the form of a collective consciousness machine known as “Own Your Unconscious”. But you tell that story through deeply individual perspectives.

EGAN: I was writing about that before ChatGPT. That's not a response, that's a parallel. I had never heard of ChatGPT, it hadn't been released when The Candy House came out. So I was thinking along those lines because the culture obviously is thinking along those lines, but in a way, it would have been very tricky to publish The Candy House now, because I feel like I would have had to somehow own or acknowledge the fact that I seem to be brushing up against some of these actual products. But that happens every time, so I'm kind of used to that.

STONE: I was going to say, I was struck by how many of your predictions in your work have come true, not only in physical technology, but also conceptually. At the end of A Visit From The Goon Squad, you explore the infantilization of culture, paid influencers... trends that are becoming reality on a global scale. I wanted to ask you how that feels, when your predictions come true.

EGAN: It feels disappointing on a number of levels. One is, these ideas were usually intended as satire. So it always feels a little disappointing when satire becomes verisimilitude. It disappoints me for the culture, because I feel like, wait, I intended that as a joke, but now it's happening. It's no surprise, though, because we're all part of one moment, and I'm responding to the same forces that inventors are, and it takes a lot more time to create a product. Even a slow writer like myself can probably get there faster in fiction, because all I have to do is imagine something as part of a piece of fiction that hopefully works, as opposed to actually creating a product and getting it out into the world, which is something I can't even fathom.

STONE: When you're writing about future technology, how much of that is research or talking to experts versus your own imagination?

EGAN: I do zero point zero zero research when it comes to technology, ever. Because if I research, then I'm really contending with present-day technology, and I don't want to. It's supposed to all be silly and fun. Also, the more tethered an imagined invention is to reality, the more responsible I feel to create something that really makes sense. For example, in The Candy House, Own Your Unconscious, in my view, is a ridiculous machine. I mean it’s the through-line of my book, not to minimize its aesthetic purpose. It's the spinal column. But if you really think about it, what the hell does it even mean to be inside someone else's consciousness? You can't just put on a headset and be there! What about the dense texture of thought that we all are engaging in all the time? Like, we don't even know how other people's minds work, whether colors even look the same. So the idea that you could just put it on a headset and be inside of someone else's consciousness, that idea doesn't hold up for a second. And I try to keep the narrative moving fast enough that we hopefully don't think about the absurdity too much. Although I also don't care, because the machine is a prop, I admit that it's a prop at the end. It becomes clear that the only machine that's really operative here is the machine of fiction, which indeed can put you inside other people's consciousness. No machine that we know of can do that. So the technology that I invent is always driven by my own aesthetic needs, and the machine I’m using is fiction itself.

Now we're actually back to cost-benefit. I just mentioned that first person narration has limitations. Third person also has limitations because you have a lot of flexibility, but you're not actually trying to ride the wave of someone's thoughts. It can be done, I mean, I guess what they call close third, but it's not quite the same, especially in an omniscient third person point of view. The prop of Own Your Unconscious gave me a way of doing both at once because I can move inside any perspective I want and then, with the “machine”, I'm suddenly riding deep thought waves of individuals because supposedly we're inside their consciousnesses. So as a fictional device, Own Your Unconscious is delicious. I can now officially do whatever the hell I want, and there's a rationale for it. There's an aesthetic justification. Of course, we can all, as writers, do whatever we want, always, but the question is, can you get away with it? Can you pull the reader into it and hold their attention, or does it just feel like chaos?

STONE: How did you come up with the Own Your Unconscious device?

EGAN: I think one of the lightning bolt moments for me was working on the chapter called “What the Forest Remembers”. In that chapter, I'm inside the mind of the only character who's a major character in both Goon Squad and Candy House, Lou Kline. I was curious about the events that led him from what seems to have been a conventional 1950s married life into being the 1970s wild man that he becomes. So I wanted to see that, and I was writing about him in the forest with his friends, getting stoned for the first time. I kept having this feeling of, like, who's telling this story, and why are they telling the story? And that's a feeling that you don’t want to have for too long in any work of fiction– it can be a sign that we don't feel in strong authorial hands. We feel a little bit unmoored. I found myself writing 'how do I know all of this?' And I suddenly realized, oh my god, this is [Lou's daughter] somehow looking through his eyes and seeing these events in his past. So now I am in first person and third person, multiple points of view simultaneously. This is why I love the machine.

I remember when I wrote the end of that chapter, I actually cried, because I realized that on some level– I mean, I don't write about my own life, but this is about as close as it gets because, [the narrator] is a little older than I am, but I’m squarely in the generation that was raised by men like Lou Kline. No one knew how to do divorce, people would move across the country, there was no “co-parenting” – I thought that term was a joke word when I first heard it. It was that feeling of people beginning their adult lives and assuming these would be their lives, setting up a home and planting things and having kids, and just that agony of realizing none of it lasted. It's painful to think about.

STONE: It's interesting that you point out traces of yourself in the story, because you've spoken about not enjoying writing about yourself. I was thinking about the mass proliferation of autofiction right now, which is obviously a sign of the times, but maybe also younger writers generally tend to write about themselves. When you were starting out, how did you crack into writing about the other? Is there an early story of yours that sticks out in your mind where you're really stepping into someone else's shoes?

EGAN: I think for me the whole impulse to write is a desire to escape. In a way a better word is 'transcend', because the feeling of being lifted out of my own experience into someone else's is really exciting. It's euphoric. It feels like being able to fly. It's the illusion of having a superpower. It's one of those things humans can never do, and I'm doing it. I'm actually living other lives, in addition to mine. So, I guess what it really comes down to is, I was never interested in writing about myself. I thought the whole point of fiction was that you weren't writing about yourself. I get a little mystified by all the autofiction, although of course it’s not new. In Search of Lost Time is trillions of pages of wonderful autofiction. So I'm not questioning the validity of that, I'm just kind of marveling that it holds writers' interest. The reader can't tell the difference, we just want to go somewhere fun and alive. And more power to every writer who finds their portal into being able to do that kind of work. If it's autofiction, god bless you, I would never know the difference! I just don't quite get it. And that's purely because, for me, the entire thing is about transcending my own experience. If I could only write non-fiction, I would be a reporter. I would be a reporting journalist, which is something else I really love and have done a fair amount of. But I don't think I have enough interesting things to say about my life. The scale is not large enough to satisfy my fictional needs. I need way more. Because it goes without saying that I have my own point of view, that's like the one thing that everyone has in their toolbox. Actually, that gets at an aesthetic principle that I've noticed in myself, which is that once I have something, once something has been established, my impulse is to work against it. Because having that thing, if I could now get the opposite, that results in a kind of potency that I'm looking for. I love to try to do the opposite of what I've already done, ideally in the same book or in the same sentence. The more contradiction and contrast, the more power.

STONE: Speaking about that portal into a story, you've said that you often start with place as your entry point in. Is it always a place you've been before, or is it sometimes a fictional place?

EGAN: It doesn't have to be a real place, interestingly. For example, I went to a castle in 2001. We had a little baby, we had moved to France because my husband was doing some work there. He had one day off, and we drove to Belgium with our little baby, and we looked at the ruins of a castle. They were quite dramatic, just in the way you want a castle to be. And I started getting this feeling that I'll get when I know that a place is activating my imagination. And I thought, whoa, what is this all about? It felt like it had come out of nowhere. At first I thought oh, I guess I'm really interested in setting something in medieval times. In other words, I took the place for a literal place. But I realized it was really the Gothic that I was interested in, and the Gothic is not a real place, it's a literary place, and when I say literary, I really mean imagined, because genre is place, to some degree. I've been thinking a lot about genre. It's very interesting to do a cost-benefit analysis on different genres. I did that with my students at Penn one day and I barely said a word. They knew so much about genre I was ready to start taking notes. And they spoke very authoritatively about their preferred genres. But what's great about genre is that it gives the writer certain things that are actually very hard to do. So, for example with, let’s just say a murder mystery, the stakes are immediately high and we know why we're reading. Someone's dead. There's a murderer out there. Boom. We have a reason to be reading this book. That's a lot to have from the get-go. But then there are huge challenges that go along with writing a murder mystery, and unfortunately I'm really understanding those firsthand! It's very difficult to achieve that combination of surprise and inevitability that is essential to a satisfying solution. It's true in any work of fiction that you want that mix of surprise and inevitability. I think that's much harder to achieve in a whodunit genre because psychology often falls by the wayside in murder mysteries. And that's why one is very rarely tempted to reread them. It's also why mystery writers so often resort to psychopathic killers. Because psychopaths can appear like normal people. You don't have the job of actually creating a psychological scenario in which murder makes sense. They just like killing people. Anyways, one thing that certain genres give, and the Gothic probably above all, is a readymade place. We all know what the Gothic is. It doesn't mean that every trope has to be there, but if I just say “Gothic”, you and I probably are thinking of certain things in common. Almost always, there's an old building at the core. So as someone who for whatever reason thinks very architecturally, I loved being in the Gothic. It was so much fun to be in that imaginative space. So it does not have to be a real place. That's the answer.

STONE: I’m thinking about the cost-benefit of a genre like science fiction, which some your work is classified under. I feel like there's often a cost of emotional depth in that genre as well, but you seem to navigate that very well, you're always very based in the characters' emotional realities.

EGAN: I think ideally the emotional depth should never have to be sacrificed for any genre. But it's very tricky. It's interesting, fantasy and science fiction particularly were among the genres my students were most passionate about. And we talked about how, for example, dystopia is often present in a sci-fi work. You get tons of good stuff right off the bat with dystopia. First of all, interesting backstory: how did we get to dystopia? High stakes. Usually in a dystopian environment, everyone's fighting for survival. Inherent drama. Every genre brings inherent drama, the question is what kind of inherent drama, and with sci-fi often the inherent drama is a battle of some kind. It's often quite a Shakespearean drama, really. I'm thrilled to be classified as sci-fi, although I don't think I deserve it, honestly, because I don’t know the genre well enough to have contributed meaningfully to it. I did read a bit of it with one of my kids, I got into it with him– these books about an elf named Drizzt, by R.A. Salvatore. And they were kind of incredible. The world building was so sweeping. I loved the willingness to encompass eons and millennia and multiple generations, creating new kinds of creatures, I love that freedom of the imagination. I think the problem for me with the notion of sci-fi may have to do with place. When I picture science fiction, the feeling that comes along with it is kind of barren. I don't like empty environments. My association with Sci-Fi often feels planetary and lonely. And that doesn't work for me. I think I'm only understanding this right now, as we’re talking!

STONE: I studied acting in college, and in the Stanislavsky technique, there's a lot of focus on place. One of the major exercises for getting into a character is to sit yourself down in a place where the character would be and then imagine, in detail, the space and all the objects in it, to mentally move around the place and explore it.

EGAN: That's really interesting to hear. For me, the reason place is so generative is that if I focus on a place that feels atmospheric and I start by just describing it, the question immediately becomes whose eyes am I looking through? And so place yields character almost immediately. And then once I'm inside a character, anything I imagine in terms of speech or action is the beginning of a plot.

STONE: In The Candy House, you use this sense of place to speak about some version of the internet, which is a sort of location-less or omnipresent thing.

EGAN: That's a weird thing about the internet. And I think it's probably one reason that, as opposed to being drawn to online things, I'm– repelled is too strong a word, but– I'm bored. I even used to feel that with television, although my first experience of the Gothic was Dark Shadows, which was a very cheesy soap opera. But back to your point, I do think the placeless nature of online experience is one reason that I just cannot make myself care about, for example, social media. I'm not good at it because I don't care about it. I'm not interested in reading other people's social media. Strangers, that's different. But people I know, if I have to look at Instagram to figure out what you're doing, it’s time for us to have a conversation.

STONE: You once published a story on The New Yorker Fiction's Twitter account, as a series of tweets. Writing for Twitter has become a highly specific, stylized thing, almost its own genre now. Why did you want to try that format, and what was the experience of actually being published in that way? Did you, did you look at the interactions of each post? Like, was it nerve-wracking?

EGAN: So first of all, it was not Twitter as we know it now, because it was Twitter at 140 characters. This was in 2012, which I think was fairly early in Twitter's life. The reason I was moved to write in Twitter- there were a lot of reasons. One is just that if I find any genre, I always wanna try to bend it to fiction. And the reason to do that is because I find that any sort of extreme structure only works if I find a story that can only be told that way. For example, the chapter that's in PowerPoint in Goon Squad, there is no way I could have written that conventionally. It would be sentimental, boring, very little happens, but you can't depict action in PowerPoint. So it was a case of structure, form and content working together, and I actually got to write a sentimental chapter that is normally not the kind of writing I do. So when Twitter came along I thought, wow, I’ve got to find a way to use this!

STONE: I would compare it to writing poetry versus writing prose. You have to find a certain memetic quality to your words, because the attention span on there is still very short.

EGAN: Yeah, there was a real inadvertent poetry to those shorter tweets that I think has been lost in the longer format. It also felt very new. And so I thought, okay, this is like low-hanging fruit. It was hard, because the question is what story requires telling in 140-character utterances? And the only possible answer was a list. And it happened that I was already interested in lists. I actually had written the story in the form of a list called “To-Do." I'm an insane list keeper. On my computer I have almost a thousand lists on my Notes app.

STONE: I was going to ask if you ever write in the Notes App.

EGAN: Um, let's see, I have 1,075 lists in Notes. Of course, very few of those are active, and I love that about notes, that things fall away, so it becomes a list of lists, and there's something so poignant about discovering an old list. So sometimes I'll go back through my lists, and I discovered a list I had been keeping called “lessons learned”. And the goal was to keep track of things I wanted to do differently. One of them was “Buy a narrower Christmas tree”. I thought, oh yeah, that was that year when we bought this tree that became incredibly fat and it blocked all the light in the room, so we had a nice tree but the room was really dark. And I had one note, it said, "Put train ticket in bag night before ALWAYS”. And I loved that because I immediately knew what went wrong, even though I had completely forgotten it! There's so much inherent storytelling in a list. A grocery list tells you a lot about the person who is buying those groceries. That was kind of how [the story] unfolded, in the form of a list of lessons the protagonist learns from each action she takes, so that the action is only described reflectively– never directly. It took a year. I ended up sending it to the New Yorker without saying that I wanted it tweeted. And they liked it, and then I said, well, there is this one thing that I want to happen… And the New Yorker Fiction didn't even have a Twitter account yet. They created the New Yorker Fiction Twitter account for that story, and they tweeted it out over eight nights, an hour each night if I’m remembering correctly, one tweet per minute. I think that the consensus among Twitter aficionados was they liked the content, we didn't get rage or like What the fuck are you doing. But I think the consensus was one tweet a minute was too slow and probably one every 30 seconds would have been better. It felt like a worthy experiment, and I was so grateful to the New Yorker for getting in there with me and being willing to do this. That kind of ghostly serialization, it was fun.

STONE: You've said that you write out everything longhand to start. Turning back to your current project, I was wondering if you're working out of one notebook at a time, or if you switch between notebooks.

EGAN: Alright, I'm going to give you the whole shebang. So what I start with is this [holds up yellow legal pad] and this is notebook 18. That's the last one of this project. And each notebook is 50 pages.

STONE: So you always do a yellow legal pad?

EGAN: Yeah. Now, I’m in this phase, [holds up typed page covered in handwritten notes]. Basically, this is first draft, and the markings you’re looking at will bring it to draft two. So when I type in these changes, I’ll number it as draft two. Draft one of this group of scenes is 56 pages long. I would expect this chapter to end up being like 22 to 23 pages, so a huge amount of condensation and cutting is going to happen. And around draft five or six I might bring it in to my writing group. And then I'm also working with an outline. [holds up typed outline] This is only 41 pages, and it includes a timeline of when everyone was born, and major events. This is a really messy phase, where I'm going from mayhem, basically improvisational crap, to something that hopefully is at least readable enough to figure out what the hell it is.

STONE: How many drafts do you usually do per chapter?

EGAN: In the end it's probably up to like 40, maybe more. I mean with some chapters, i get up in the 70s. It depends. The fewest drafts of anything I've ever done, from initial outpouring to final product was the chapter called “Rhyme Scheme”, in Candy House. Very strange because the first person narrator is a young man whose brain works very differently from mine, but I found Lincoln to be just effortless to channel.

STONE: Is this new book going to be a linear story, on the page?

EGAN: Yes, I think so. After Candy House, I'm more in the mood for something linear and not fragmented. Also, I mean, in the whodunit genre, I don't know how fragmentation would be much of an asset. It's always that question, like, what is this technique bringing to the story? How is it helping me tell that story? There's something fun about traditional storytelling, whatever that even means, because the earliest novels are so crazy, that I think we've gotten bizarrely conventional, actually, and I'm not sure why. But writing things in a linear, straightforward way, I find to be a little harder. Fragmentation gives you a lot of shortcuts. It's like painting abstractly when you can't draw figures. So I have to be careful that I'm not just doing it out of habit.

STONE: What does it look like when you're researching a story that occurs in a historical time period like this one? How does your research begin or unfold?

EGAN: Very randomly, although I do actually have two people doing some research for me now. I would say there's a lot of crime reading, and then I start noticing elements of the period, trying to internalize locutions, and there's a certain amount of actual historical detail that I need. It's usually a combination of archival research, conversations with knowledgeable people– for example, my stepfather is going to be 95 next month, and he's been a fantastic source because his memory of San Francisco in the 1950s is very good. So he has given me a lot of color– even just names of long-gone businesses, I have a whole list. I always take notes when I'm with him. And he'll just start talking about, for example, where ladies liked to have lunch at this time... these little details that I write down. Tour books from San Francisco, photos... there's so much that I can look at. So I do it kind of peripatetically, but ultimately I'm quite systematic. I just haven't gotten to that systematic point yet. I've got a wonderful researcher, who has done research on things like air travel in the early 50s, which was obviously so different from the way it is now. And she's just beginning to work on cars. So it feels like sort of a mishmash, and yet somehow in the end, I end up feeling like I have a strong body of knowledge that feels pretty well organized, even though my approach to it is casual. Casual, and then organized.

STONE: When did you know it was time to put aside the other novel you're working on, about the 1870s, and just focus on the whodunit?

EGAN: When I started typing this one up. I felt like, I'm going to just need to work my ass off on this to get it done. I can’t be working on two projects at once anymore. But I worked on Candy House and Manhattan Beach at the same time, for like a year and a half. And then I did the same thing, I put aside the Candy House material, untyped up. And here, too, I haven't even typed up this other project. So I'm just going to let it ferment, and work on this one, and then I'll have something to go back to right away.

STONE: Do you think that there is a possibility of the Goon Squad/Candy House characters showing up again in a later work of yours?

EGAN: Yeah, I do think so. A big challenge is that there's no way to really draw the circle wider without it just kind of dissipating. I think Candy House is the widest I can get it. So probably working with that world again would involve focusing on just one part of it. And that might feel a little weird to fans of these books. But I'm assuming that I'll give it a shot. I think it's just several books away.

STONE: In The Candy House, you explore characters who work to collect people’s data and creating a collective consciousness/ memory database, and characters who seek to elude that system and resist being uploaded. Personally, which side are you on?

EGAN: I'm interested in both. I really agree with something the character Lincoln, who turns out to be my alter-ego, says: that if facts solve a mystery, then it was never mysterious. The real mysteries remain mysterious, no matter how much we know. That's not something I ever would have said or thought before writing it. And that speaks to the joy and the sense of mental expansion that is my reward for writing fiction. Because that's the last kind of thing anyone would expect to hear from me. And yet, I now not only wrote it, I also agree with it.

JENNIFER EGAN is a Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist and the author of A Visit from the Goon Squad and Candy House.

JOHANNA STONE is a Los Angeles-based writer and a contributing editor of Animal Blood.

← back to features