ARE CORPORATIONS PEOPLE?

Nevin Kallepalli

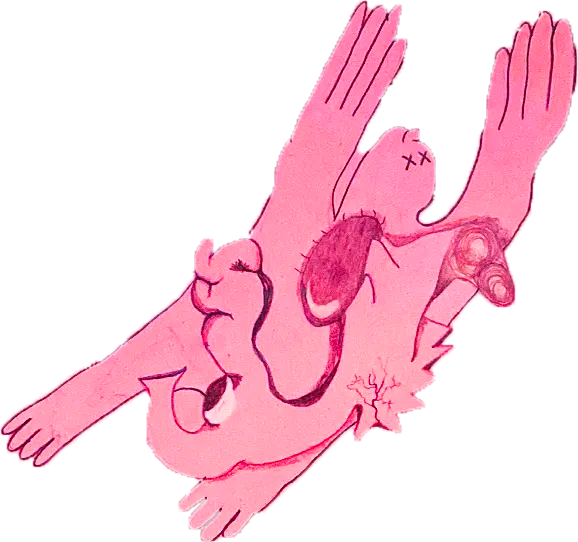

Are corporations people? The root of the word corporation is of course the Latin corpus, but is a body a person merely by virtue of having a body? Technically, corporations are bodies comprised of multiple bodies, which seems too vulgar to describe the modern corporation. Though the nation’s first corporations were exactly that–colonial plantations–and it is upon this structure that the American financial system is built. Are corporations then, bodies without soul? Corporations are people when allowed to exercise certain rights as an individual would, such as donating money to a political campaign or observing religious customs in opposition to federal mandates. And so too can individuals act as corporations when declaring themselves LLCs, and in a sense are corporations as one’s public personas on Instagram or LinkedIn are integral extensions of the workplace. What then is the difference between worker and the workplace? Where does one begin and the other end, as most white-color labor can be performed anywhere at any time via zoom and the various clouds? When did corporations become people, and people corporations? Legally, it was in 1886. The verdict of Supreme Court case Santa Clara County v. Southern Pacific Railroad Company applied the reconstruction-era 14th Amendment (ratified after the abolition of slavery to expand civil rights to all U.S. citizens) to the Southern Pacific Railroad Company in a tax dispute. This esoteric-yet-landmark decision set up the framework through which sums of capital oscillate between the statuses of person, company, and state. Take any train in New York City and you will be bombarded by ads for start-ups with human first names. Each embodies the same empty familiarity in the attempt to seem totally unique. No two fingerprints are the same. Nate, Casper, Cora, Oscar. It is impossible to discern the services they provide from their names alone, which range from health insurance to mattresses. A biracial lesbian with an undercut is photographed with a soft, dispersed flash against a canary yellow Seamless. I look at her, And she’s looking up. What is she doing? I search the advertisement for any indication of what I’m being sold. The only text provided is cryptic: Baby, it’s cold outside. Just gift with a text. no address needed. The name nate appears in the corner, in a bespoke typeface. With the limited information, I conclude that what I’m supposed to think is that nate is youth-oriented, inclusive, and was founded by a he/they named nate. And nate must know Christmas is coming up. I think. Whatever service they provide is beside the point. A quick google search leaves me as confused as when I began: Why nate? | nate is the first artificial intelligence online shopping tool that centralizes purchasing onto a single platform, enabling users to buy a product from any e-commerce site with the click of a button.Do you know nate? I met them on the train. What is the purpose of assigning human qualities to the products in our homes, human behaviors to the portals through which we consume? Is it speculative? Is it aspirational? Science fiction has crudely rendered countless cautionary tales in which automatrons have transgressed the boundary of objects, and humans of mortals. The nightmare of man-as-machine and machine-as-man relies on a materiality that is no longer relevant. In the future, we will map emotional sentience onto algorithms and data aggregates, the invisible tools that both anticipate and manifest our most intimate fears and desires. Why shay? | Shay is the first artificial intelligence security tool that centralizes the financial transactions, geographic mobility, and digital correspondences of an individual or data set, enabling law enforcement to forecast crime by type, time, and location with the click of a button. In September of 2021, a video went viral of a concerned citizen defacing a set of subway advertisements for the dating app OkCupid. Similarly to nate, the campaign featured a mélange of hip-looking interracial couplings, photographed against a monochromatic powder blue background (interestingly, OkCupid’s representation of miscegenation always includes a white partner–any kind of race mixing among people of color is apparently beyond the company’s imagination). Each panel was emblazoned with declarations such as EVERY SINGLE PANSEXUAL, EVERY SINGLE VAXXER, EVERY SINGLE NON-MONOGAMIST, EVERY SINGLE SUBMISSIVE, EVERY SINGLE PERSON. The incensed woman in the video moved through the train cars ripping down the vinyls, remarking, “this is gross, for kids to be looking at this, is this okay? This is propaganda.” Let us take a moment to annotate her line of questioning. This is gross. Yes, it is gross, and that is what gives the advertisement currency, despite OkCupid’s PR strategy of claiming that these advertisements are un-gross in normalizing fringe sexual identities. Any sort of criticality is categorically bigoted. For kids to be looking at this, is this okay? Here the assumption is that the child is a tabula rasa. In their innocence, children are not primed to make a decision about their own sexual desires, let alone map the proclivities of others onto themselves. I would go so far to say that in this iconoclastic woman’s reaction to the advertisements, the child is a stand-in for any subway rider, who shouldn’t be forced to address their own sexual desire in a public space such as the MTA. The child is often the foil for how far the pseudo-irreverent media class is willing to go. Here OkCupid is attempting to do two things that are at odds with one another. They are trying to be evocative while insisting that sexual exploration can be de-fanged, something the entire family can participate in. The OkCupid user is both edgy and wholesome, a community-minded individual. Like say, a vaxxer. This is propaganda. Is this propaganda? And if it is, is she not seizing the means of production in tearing down the advertisements? Personal politics aside, misguided as she may be, what is at the core of the rider’s intervention is this: to see one’s sexual desire (an experience that should remain very close to the ego) externalized, condensed, multiplied, and sold interminably robs intimacy of its meaning. Perhaps what she is asking is why must we make desire so legible? Melissa Hobley, OkCupid’s Global Chief Marketing Officer, was quick to clap back on Twitter: “In light of the recent homophobic rant sparked by our ad campaign celebrating all kinds of people and all kinds of LOVE, @okcupid is making an even bigger commitment to being inclusive. So thanks for the craziness. Also, put on a mask. You owe the @MTA $50.” The advertiser is the most adept reporter of the current moment (much to the chagrin of the self-aggrandizing journalist, though the line between advertising and journalism is increasingly murky). The OkCupid campaign is part of a larger ad-scape, that has a distinctly annoying millennial sensibility. These advertisements’ tone of voice weaponizes insecurity and quirkiness, which themselves are compulsive reactions to the subtext of American life: violence and failure. While OkCupid encourages one to cement their identity and monetize it, the Seamless ads one train car over attempt to discourage human contact all together. One proudly reads 8 MILLION PEOPLE IN NEW YORK AND WE HELP YOU AVOID THEM ALL. Unintentionally, OkCupid and Seamless are working in tandem to exploit the anxieties of a generation that have been exacerbated by hyper-visibility and now, hyper-isolation. SATISFY YOUR CRAVING FOR ZERO HUMAN CONTACT. And besides, you deserve it. It’s self care. There is power in admitting defeat. You can be who you really are indoors, because everyone can and is watching you. The domestic space can be your entire universe, and besides, it’s safer that way. Think of the pandemic! You are a hero. You are protecting other people. Well, besides the delivery man. Or woman. Or person. Are corporations nations? The East India Company acted with the might and impunity of a nation when it colonized all of South Asia, effectively conscripting millions into bondage. And while the U.S. decided that outright imperialism was gauche and European, 19th century American corporations such as the United Fruit Company propped up their own Banana Republics amid the ruins of de-colonized Latin America. Certainly, Amazon has all the trappings of a nation-state: the allegiance and sensitive information of its millions of customers, trillions of dollars, and a bounty of real estate. The only thing it lacks is a border.

← back to features