AN ART HISTORICAL NORTH STAR

Olivia Barrett

I enjoy that [running an art gallery in LA] means working in the shadows of something because the dominant cultural industry is not art – assuming one can say ‘Hollywood’ as an industry still exists… another conversation. The conceptual runoff from that is so fascinating.

TESS POLLOK: I'm really curious about the history if you want to talk a little bit about, like, before you opened or when you opened and what makes you want to start your own gallery. And wait, I'm a little fuzzy on the details here, but you curate and direct the shows as well, right?

OLIVIA BARRETT: Beginning at that inflection point of moving to Los Angeles fourteen years ago, or maybe just before, I came from Melbourne, a very different cultural and practical environment. My entry point into contemporary art had been writing and literature. I was studying philosophy and art history while many of my friends were in art school. I would produce texts or publications or exhibition conceits to buttress their work. I had no idea about the art market, which was anyway a small and siloed industry in Australia, as I remember it, but I worked for the Australian Center for Contemporary Art, a kunsthalle, and Uplands Gallery, the only interesting, scrappy, commercial art gallery doing anything that felt resonant in Melbourne for me at that moment. And because of the public funding structure for the arts in Australia then (which is no longer the case), there were micro grants one could apply for and a general resourcefulness to pursue experimental, conjectural or impressionistic projects. So I made exhibitions and publications, and publications-as-exhibitions, then fortuitously, someone offered me a job in LA, a city that had already seduced me when the offer landed.

POLLOK: When did you open the gallery?

BARRETT: 2014. The first exhibition was a dual presentation of works by an artist collective that no longer exists, Body by Body, and lithographs authored and printed by Odolin Redon. I realize now in retrospect this set the tenor for how the program would unfold, layering in different historical positions or these kind of juxtapositions in order to produce a frictional dialogue with artists in the program, that could also mitigate some of the kind of amnesia that I was sensing in art making and art reception at the time. The gallery was founded in 2014, peak web 2.0.

POLLOK: Why amnesia?

BARRETT: Amnesia because it felt like there were so many artists who were making work that so closely resembled historical artists' work without disclosing any kind of relationship. Like everything was just in this orbital state, untethered from predecession. I felt uneasy about how the lubrication of the media environment matched the lubrication of the market at the time and I was feeling the slippage of these holding points of meaning and value and the exchange between those things, as though everything was slurped into continuous momentum. I’m sure that’s delightful for some people’s constitution and one isn’t more virtuous, but clearly I was feeling some subconscious imperative to insert historical positions, and that really shaped the exhibition program as well as the stable of artists ongoing. Jacqueline de Jong, for example, was an artist still making work when we reached out to her to inquire about her earlier practice, the Situationist Times and her Série Noire paintings. So it goes both ways – in the search for historical touchstones we get slingshotted back to the present and end up exhibiting the entire arc of her career, including the paintings she was making at the end of her life.

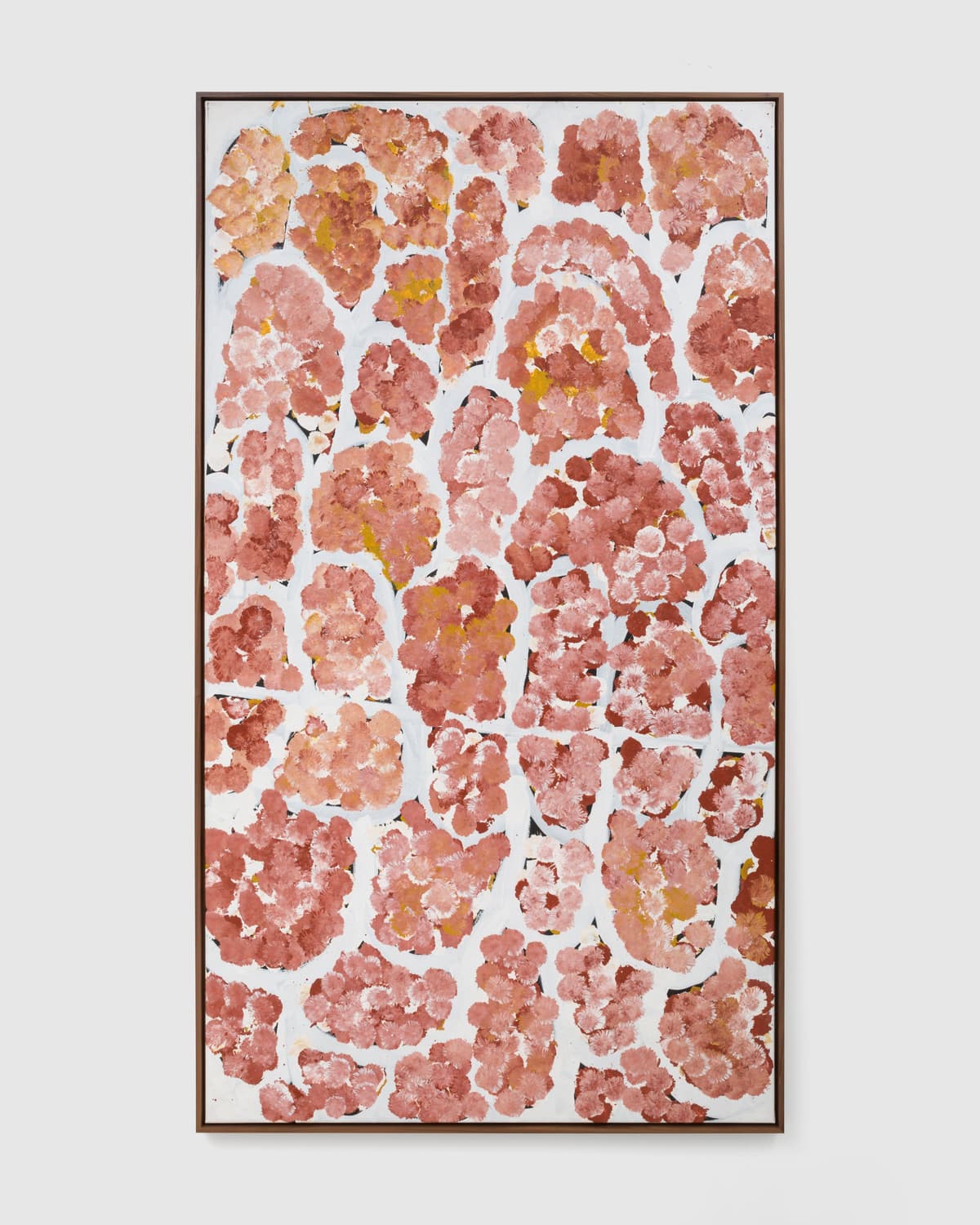

Minnie Pwerle Emily Pwerle Molly Pwerle Galya Pwerle. Courtesy of the artists and Château Shatto.

POLLOK: What do you see as some of the through lines between exhibitions with different artists. Do you see any at all?

BARRETT: I would say I look more for a kind of dynamism than a through line. I look for chemistry and sometimes that can be a kind of dissonance and sometimes it can be more continuous and connective. Mostly, I believe in foregrounding great works but also the theatrical potential of making exhibitions. It’s why I'm committed to the slightly impractical but poetic format of the gallery. This also accounts for why we moved recently to a site that would invariably attract a larger audience of people walking in the door.

POLLOK: What and when is your next show?

BARRETT: Our first exhibition with Will Stovall, ‘Lifeworld Variations’, opens November 1. Will is a DC-based artist who uses sculptural substrates to configure perceptual encounters with paintings. Prior to dedicating himself to an art practice, Will completed a doctoral dissertation on the subject of the ‘lifeworld’, a phenomenological concept which emphasizes how internal experiences and external systems shape one another. The work embodies how we relate visually to our knowledge of ourselves and the world. It’s wonderfully rich in thought and form. In a moment when so much political art is didactic or overstates an obvious moral position, Will has managed to make a body of work with a nuanced understanding of where politics lives in our perception.

POLLOK: Do you have any recent shows that you're particularly proud of?

BARRETT: I have to say the current show is especially meaningful to me for myriad reasons: conceptually, experientially, art historically, also my personal history of viewing this genre of painting from a young age and the people who were involved in the collaboration. It’s a love letter to what can’t be reconciled. The exhibition assembles work by four artists–Minnie, Emily, Molly and Galya Pwerle–sisters, belonging to the Alyawarre and Anmatyerre language groups in the central Northern Territory, Australia.

They emerge from what we could call a post-Papunya Tula tradition of Indigenous painting from the Central or Western desert, a phenomenon of contemporary art that has this remarkable dialectical tension that has always engaged me. It comes into existence at the collision point of two incongruous worldviews: one being the indigenous cosmology which the Pwerle sisters were deeply practiced in and the other that they were forced into participation and violent contact with, the post-colonial and post-modern conditions of Australia as a political, social and economic entity.

The practice of mark-making is already present in the Pwerle sisters before they begin painting towards the end of their lives (Minnie and Molly are deceased, while Emily and Galya are living) by virtue of the visual dimension of awelye, a ceremony practiced by women. But these paintings don’t arise from a one-to-one transposition of ceremonial marks, as evidenced by the distinct formal languages each sister innovated independently and the material reality that these works are rendered with synthetic polymer paint (a by-product of crude oil) on canvases mostly dispatched from urban centers.

Another reason I’m magnetized towards this work is because when the first works were realized in Papuyna Tula, there was a contentious debate about what was being revealed by the signifiers in these works. Because ancestral knowledge and access to the cosmology was transferred using a system of rigorous matriculation, the idea that insight could be shared outside of the language group or even gender within the language group was completely verboten. So then what begins is this complex form of formal experimentation with codes, signification, vigorous expression. The great artists of this pillar of art history then played with incredible elasticity and authority with formal possibilities that could both suggest and conceal; invite and refuse. This is a quality that I find in most art that I’m inveterately drawn to.

Minnie Pwerle Emily Pwerle Molly Pwerle Galya Pwerle. Courtesy of Château Shatto.

POLLOK: You’re bringing works by Emily Kam Kngwarray and Alan Lynch to Art Basel Paris. How do you go about selecting artists for fairs?

BARRETT: It always depends on the time and place of the fair. Sometimes we begin by reaching into the program to develop a booth with consideration of a project that has recently come into existence. This booth began with Emily Kam Kngwarray as this work perpetually feels like it’s coming into existence and the opportunity to advocate for the work and deeply consider its terms of making and its terms of reception, this felt urgent and imperative. Kngwarray’s practice is presently the subject of a retrospective at the Tate Modern and she was my first painting god. Maybe her, Bronzino and Twombly. Again, the historical anchor gets lowered in moments that feel like something needs to be moored. Then alongside Alan Lynch, I recognized both were playing in the realm where transmundane finds form in painting, ostensibly a static form, that reveals its very protean structure.

POLLOK: Why is she in your pantheon?

BARRETT: [holding up a reproduction of the painting of Big Yam Dreaming] There’s a painting very similar to this in her retrospective and I’m still shivering from being in its presence. Her paintings affirm the reason that painting exists. So much painting now works against its specificity and empties itself out. Every encounter with an EKK painting fills it back up again.

The authority and exploration, the innovation of the work she made. She only produced paintings for the last eight years of her life, having been given these materials that were more immediate and plastic than mediums she’s previously used, and these perfectly sublimated artworks poured out of her, it’s astounding. And there's no editing or revision. They're so of themselves, so embodied and visually explorative. They get consumed by the art market as abstraction but they do have subjects at their core, which speaks to the representational freedom of her vision. They belong deeply to the cosmology that defined her life practice which involves an integrated and collective existential understanding, are contingent on an ideology and politics that’s in direct conflict to this, and could only be envisioned and rendered by her.

Another thing to consider: Big Yam Dreaming was made in 1995 and she started making the yam paintings a little earlier in the 90s, the moment when the world of art and academia was enamoured with the rhizome, with Deleuze and Guattari’s thesis on it. Here she is making rhizomatic paintings, asserting that the structure of the rhizome isn’t only academic, it’s existential, and not everything of the highest conceptual order needs to be filtered through academia or Western traditions of philosophical thought.

© Emily Kam Kngwarray/Copyright Agency; Licensed by Artists Rights Society, New York, 2025. Courtesy of Château Shatto.

POLLOK: Do you have any sort of big dreams or ambitions for the gallery?

BARRETT: The dreams and ambitions mostly get shaped by the active thinking and inquisition that has to happen to keep the program and operation alive in practice and interesting to others and oneself. Working with artists means the shape of the gallery is constantly in motion. Some ambitions that I might have been harboring in the past have been realized more recently: moving to a space with visitors beyond those treating it as a destination, plus over the last few months the team of employees has really clicked into a wonderful composition of people, abilities, voices and temperaments.

POLLOK: Do you know or anticipate how exhibitions will be received? Or do you just proceed?

BARRETT: I'm not a salesperson in the sense that I couldn't sell you this watch, so I can’t lead with anticipating others’ expectations or what may appease a wide audience. I’m dedicated to cultivating markets and opportunities for artists but that begins with being an advocate for cultural material and so the threshold for me is believing in the work, thinking that it is contributive and believing in the artist’s system that they build around their work, so I trust I can follow it into the future.

POLLOK: How do you work art history into what you do?

BARRETT: Reading and writing is my natural respiratory, including art history. There are so many kinds and methods of art history, per se, but language is my habitual state of relating to things. I think successful examples of art history can be transformative of the viewing experience, not so much in a way that they premeditate how one should perceive an artwork work, but more so that what one reads in effective art historical propositions can contribute to the infrastructure of perspective.

POLLOK: I'm curious who some of your favorite philosophers or art historians are. Who do you read the most?

BARRETT: Always TJ Clark, he is the art historical north star for me. Byung-chul Han and Mark Fisher for more recent philosophy that is also cultural theory, which maybe all philosophy necessarily has to be at this point in history. This is a question I’ve had in my mind lately so if anyone has a perspective I’d be interested to hear it.

POLLOK: What do you find unique about running a gallery in Los Angeles specifically? Do you find it enriching or challenging?

BARRETT: For me, LA is not an arbitrary backdrop to a business that could be anywhere. I moved here because I was very attracted to the traditions of making and thinking here or as I perceived them when I didn't live here. Art is not the dominant cultural product being made or marketed, but there is also a real audience for it. So it feels nimble but practical. It’s challenging running a gallery anywhere at the moment because art has either become prohibitively expensive or collecting it has the increased reputation that it’s a pursuit for those who are rich beyond a profession or a vocation. And the realm of what we yearn for, collectively, phenomenologically, has been augmented by consumption habits that don’t sit well with ambivalence or discomfort, or questions that might not have succinct answers.

POLLOK: Yeah, that's a very interesting insight. I don't know that I've ever had a gallerist from here say that before about Los Angeles but I like thinking. Why do you feel that?

BARRETT: I enjoy that it means working in the shadows of something because the dominant cultural industry is not art – assuming one can say ‘Hollywood’ as an industry still exists… another conversation. The conceptual runoff from that is so fascinating. It's why it makes sense for Jean Baudrillard to be in our program. We’re already operating just downstream from a creative and commercial environment that is not so often able to reflect on the conditions of its own making but then art can always do that, is does that mandatorily. And so having an art gallery with that kind of spectral presence around, I love it, there’s so much to riff off. I mean, Aria Dean's exhibition, Facts Worth Knowing, is a great example of work that needed to be presented in Los Angeles but can also radiate beyond the limits of the city. We had a substantial number of people who were literate in the history that she was plucking from. So she wouldn't have made that show anywhere else.

OLIVIA BARRETT is the owner and founding director of Château Shatto in Los Angeles.

TESS POLLOK is a writer and the editor of Animal Blood.

← back to features